When the Mind Cannot See

What aphantasia reveals about reading, writing, and imagination

I have always liked the word immerse for its figurative sense, i.e., to involve oneself deeply in an activity. But when said activity is reading, the definition transcends the figurative to assume the extraordinary—for to be immersed is to accept a temporary alternative existence.

It’s a transition which, though mental, prompts and exercises my senses. I don’t only know there is a winding, rock-strewn stream in the fictional realm I have entered—I see it. I see how mellow sunlight spills across its surface and, like misplaced clouds, the water foams near the banks. I don’t need to remind myself of the sounds surrounding me, because I hear them. I hear the water gushing along its course, crashing into rocks; the way birdsongs cluster into a single chorus. If a character is said to sit by and reach over to touch a rock, I feel its rough wet texture on my fingertips. The scene plays in my head as a film, and I move about as though I were on set.

Until recently, I thought this manner of experiencing books was universal.

But as it turns out, three to five percent of the world’s population has aphantasia: the inability to voluntarily visualize mental images.1

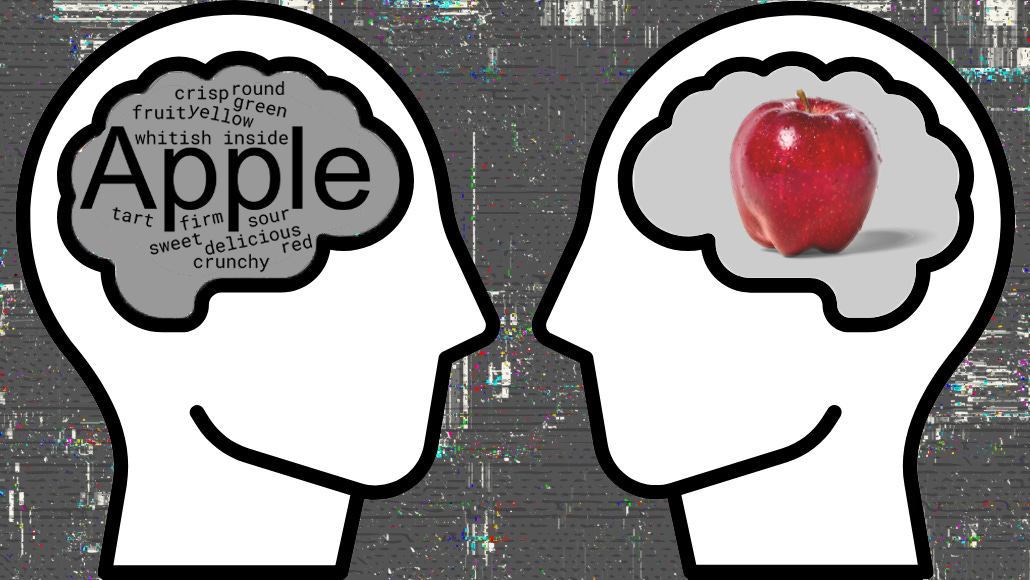

If an aphantasic person is asked to think of an apple, for instance, their mind conjures up no image. They may instead focus on the concept of an apple: that it is a fruit, round-shaped and crisp, colored red or green or yellow—and so on.

It’s not a neurological disorder, nor a disability. It’s a neurodivergence—a natural variation in how the brain processes information.

Although scientists in the nineteenth century did note differences in mental imagery strength among individuals, aphantasia as a condition was named only in 2015 by British neurologist Adam Zeman. He found that, in most cases, aphantasia is congenital and runs in families. In some, though rare, it can develop later in life as a result of brain injuries, strokes, psychological trauma, or mood disorders.

What intrigues me most is that aphantasia is a spectrum. There are people with complete aphantasia, affecting all of their mental senses. This means that in addition to having no “mind’s eye,” they can hear no voice or sound inside their head, and can imagine neither smell nor sensation. Others have partial aphantasia, lacking the visual capacity but not the rest (or some of the rest).

Since much of our cognition relies on these mental senses, aphantasia may impact the quality of memory recall, dreams, and logical reasoning—among other processes. This Daily Mail article, for example, spotlights a man who is unable to picture his wife when they’re apart, or to remember the details of important life events, like his wedding day and the birth of his daughter. But this is hardly the standard; many aphantasics possess near-photographic memory while recalling recent and distant experiences—for them, it’s specifically the voluntary formation of images not readily available or lived in that proves difficult.

When it comes to dreaming, aphantasics are also a diverse bunch: some report having ordinarily visual dreams, albeit less vivid, whereas others experience nonvisual, abstract ones. This suggests that the neural pathways involved in such involuntary visualization are distinct from those necessary for the voluntary kind, making it possible for some of those who can’t conjure up imagery while daydreaming, thinking, and decision-making to still visualize when they sleep.

But more central to our discussion is whether and how aphantasia shapes the way someone reads—how they consume fiction.

I feel inclined to rethink my definition of immerse. If some of us don’t see what they read, can their experience with books still be immersive?

I’ve come across this comment by a user on unity.com, in response to the question: “What does ‘immersive’ mean to you?” Though asked in the context of video games, I thought much of what was shared by the community applied to books too.

“Think of immersive this way: you either dip in your toe to get a taste for the water, or you can jump in and get the full experience in one go. It’s about how the senses are teased and what is used to make them go boom.”

Aphantasic readers who feel immersed in stories are, then, readers who only dip in their toes but manage to get the water’s full taste. It might not be the sensory descriptions that make them go boom, but boom they still go. The question is: how? Another matter I can’t help wondering is: can aphantasics be fiction writers?

Aphantasia is still a new science, and a lot remains unknown. With each research finding, theory, or opinion that comes up, I feel my fascination with the topic grow—for intense is my fascination with the sheer diversity of our inner little worlds: with how we reason and imagine, but mostly with how our brains enjoy and engage with the universal practice that is storytelling.

(A)phantasia across time

The prefix a— denotes absence. To understand the latter part of the word, phantasia, we’ll have to go back to 340 BC—to Ancient Greece. Aristotle defined it in his treatise De Anima (On the Soul) as a faculty that operates between perception and thought; as a kind of sixth sense that permits the happening of other mental processes.

Let’s rephrase this in common English: when you see a cat, your eyes send its picture to your brain. That’s perception. Later, even if the cat is gone, you can still see it in your mind. That inner picture is phantasia, which is Greek for making something visible. And thanks to that picture, you can remember whether it was the cat’s left or right ear that was chipped; you can decide if it was cute (of course it was); you can analyze your interaction with it and consider whether it was friendly.

Phantasia is thus the mediator between sensory perception and introspection.

“The soul never thinks without an image.”2

This means, to Aristotle, that the mind relies on a picture to think, remember, and reason. But the catch is that he did not limit that picture to the visual type; it could be auditory, or a memory, or a feeling. So when we think about, say, the local park, or a friend’s voice, or a favorite food, our brains are using phantasia—little mental pictures and sensations—to help us relive a past experience and analyze it, envision possible future scenarios, and make decisions in the present.

For centuries, this understanding of visualization went uncontested. It did not occur to scientists that a small but significant portion of the population lacked phantasic capacities, performing ordinary mental functions in unordinary ways.

The earliest observation of image-free thinking dates back to the year 1880. British psychologist Francis Galton, known at the time for spearheading human intelligence research, conducted a study now famously referred to as the “Breakfast Table Questionnaire.” He gathered a hundred men (including his cousin Charles Darwin) and asked them to visualize their breakfast table from that morning, then to relate the vividness and detail of what their minds showed them. He recorded a wide range of responses: some were striking descriptions; others fainter ones. To his astonishment, a minority admitted seeing nothing at all.

Galton’s conclusion was that “the powers [of visualization] are zero”3 for a few individuals, and that this variation was a natural, albeit rare and extreme, phenomenon.

Despite the importance of his discovery, the study of phantasic abilities was largely neglected afterwards. Galton’s introspective method was considered unreliable when behaviorism—whose proponents included B.F. Skinner and John B. Watson—became the dominant analytical framework for most of the twentieth century. Behaviorists argued that if a phenomenon could not be seen or measured, it didn’t belong in science—and, well, since mental imagery isn’t exactly an outward occurrence, it was cast aside as unworthy of being explored.

Other factors that further pushed aphantasia out of the picture (no pun intended) was the lack of medical imaging tools, which would have “measured” mental imagery strength in some way, and that scientists saw no urgency to investigate a condition that caused no obvious impairment. It was simply not the right time or environment for this topic to thrive—but I can’t stop thinking: had Galton’s luck been any better, we could’ve possibly been spared of the eugenics movement he later founded…

That said, the study wasn’t altogether abandoned: later decades saw some scientists, such as A.C. Armstrong in the United States, taking interest in Galton’s findings and replicating his experiment. Here and there a new paper was published, commenting on the distinctions between visualizing and conceptualizing thinking styles. All reached a similar conclusion but failed to make sense of it. Failed to give it a name.

It all changed in 2009, on the day neurologist Adam Zeman was visited by a patient with an unusual story to tell. “Patient MX,” as he was publicly called, was a 65-year-old man claiming he’d lost his ability to see things in his head after undergoing heart surgery. Yes, heart surgery.

How was his brain affected if it hadn’t been operated on in the first place?

Zeman didn’t know it at the time, but this was the first documented case of acquired aphantasia. He termed MX’s condition as “blind imagination,” and in the following year published a case study in which it was thoroughly analyzed. It’s believed that MX’s brain might have suffered from brief oxygen deprivation or emboli (tiny clots or air bubbles that don’t exactly cause a stroke, but are enough to affect specific neural pathways) during the operation. Instead of damaging vision itself, the surgery appears to have severed the brain’s ability to internally activate visual representations. It impaired his phantasia.

This ordeal proved something significant: visualization is neurologically fragile—an ability that isn’t always guaranteed.

For several years Zeman fully immersed himself in the topic. It was in 2015, after performing a landmark study, that he confirmed the inability to visualize could also be congenital.

And so he coined the word aphantasia. It was a scientific breakthrough that paved the way for a closer understanding of human cognition.

But more importantly, it helped millions of aphantasics around the world feel seen.

The phantasia spectrum: how vivid is your inner world?

Interestingly, aphantasia was not Zeman’s sole discovery: he realized that just as there are people who cannot visualize, there are those who overdo it. He coined hyperphantasia as the ability to see in one’s mind so vividly that the experience can rival real-time sensory perception. It’s the polar opposite of aphantasia—and yet, as rare.

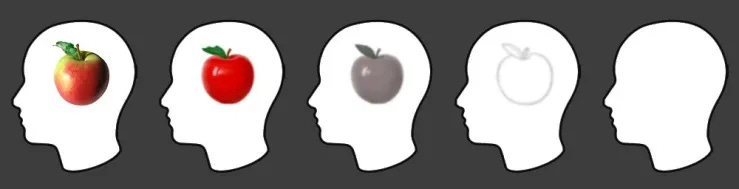

The majority of the world’s population falls somewhere between these extremes. But even then, no phantasic person is like the other. Let’s use the apple example again: one person might see only the fruit’s outline when asked to envision it. That’s still phantasia, but it’s dimmed down in comparison to whoever can see its interior as well, to whoever can think of it in color, and to the one whose internal vision is so detailed they make out even texture and shading.

The diagram from before can thus be revised as shown below:

But it’s still not a comprehensive graphic. I think it improbable that the staggering variety of imagery strength can be captured in illustrations or diagrams. A promising attempt would, however, look closer to a chromatic spectrum—but one that is all-encompassing instead of horizontal, in order to account for the numerous combinations that there exist of phantasia across all mental senses, not only the visual.

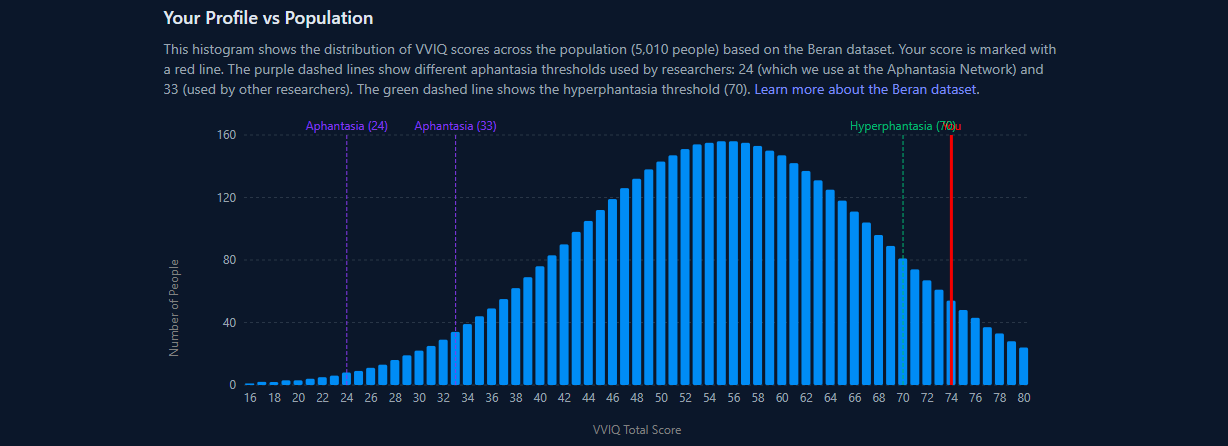

In 1973, British psychologist David Marks found a way not to represent phantasic diversity, but to quantify it. He developed the “Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ),” a simple five-point scale quiz that has since then been used as a sort of official unit of measurement for mental imagery strength.

And you can get tested any time.

Aphantasia Network, a leading global community dedicated to exploring aphantasia and educating others about it, has made the VVIQ available to all users. You may access it here.

The test is simple—a casual questionnaire asking you to try and form a mental picture of different settings, objects, or people. The first question, for example, requests that you select a relative or friend (or someone you see regularly), and visualize the exact contours of their face, head, and body. You answer either 1 (for no image) or 5 (for a very vivid image), or a number in between. Your result is then quantified and presented in a histogram.

A score of 24 or lower indicates aphantasia.

A score of 70 or higher indicates hyperphantasia.

Anything within that range is phantasia. The closer you are to 70, the stronger your visualization.

I did it myself a few days ago. A score of 74 has placed me as a hyperphantasic. Now I have to say—although the VVIQ is today’s gold standard for testing visualization, I remain a little skeptical of its accuracy. It is, after all, reliant on self-reporting. I don’t believe it captures the true complexity of the condition(s), especially as it only tests for the mind’s eye.

But if I were to assume this result is accurate, then I wouldn’t be too surprised with my being hyperphantasic. My mind is loud with images, sounds, and sensations I can’t always suppress. Daydreaming, like reading, is almost a physical experience: scenarios—vivid, life-like, even sequential—find a home in my head. A home, because I find it unpleasant to leave. I feel myself transported even as my body in its physicality remains where it is. Sounds, smells, and sensations I dislike (I cannot for the life of me tolerate the sound and feel of cutlery touching my teeth) make me squirm, but I immediately follow them up with those I do like—and find myself comforted.

If hyperphantasia is indeed something I have, then I have to admit it’s not an altogether adventageous thing. The compelling nature of the images often distract me from important tasks (but hey, at least I have a creative excuse for procrastinating), and I have been multiple times called out for drifting off mid-conversation.

Since doing the test, I’ve been reading up about hyperphantasia and its innumerable variations. Apparently, several hyperphantasics also experience synesthesia, a phenomenon in which the stimulation of one sense causes an involuntary response in another. It’s the science behind why some people can “hear color” or “smell music.” I personally don’t experience this, but it’s fascinating. There are also visual hyperphantasics who are aphantasic when it comes to sound—they’ve no mind’s ear. There are, too, the opposite: hyperphantasic in mental sound, but aphantasic in vision. The variations are too many to count—and the science of phantasia is unpredictable because genetics are unpredictable. There’s no telling what more combinations can come to exist.

Regardless of whether I’m hyper- or ordinarily phantasic, one thing remains true: I am fiercely curious about the other extreme extreme—total aphantasia—and particularly how it affects the reading and writing of fiction.

On aphantasic readers and writers

“I cannot really imagine what it would be like to read with visual images.”

Research has shown that a common theme among aphantasics is a dislike for books of fiction.4 The sensory descriptions writers use for setting and character creation are but laborious chunks of text for many aphants (wait, I just realized—aphants sounds better than aphantasics, doesn’t it?), prompting them to skim or even skip those paragraphs. Anecdotal evidence suggests that they prefer non-fiction, conceptually-rich books—the factual over the imaginative.

But that, as I have come to find out, is in no way definitive. Several aphants are avid fiction readers and have been so since childhood. Writer and academic Jemma Rowan Deer, whom I quoted above, has been reading since the age of seven. She has completed a PhD in literary studies and composed criticism for years while being aphantasic. In an article for Orion Magazine, she’s shared her personal experience with discovering she has the condition—with discovering that, for most of her lifetime, she has been engaging with literature in ways unlike the norm. The substance of her essay is an affirmation: the lack of the visual element has never stopped her from enjoying books. It has simply allowed her to enjoy them differently.

“[…] I have no problem imagining any aspects of a book that are nonvisual: the weather patterns of human relationships, the melancholy weight of an unrememberable past, the weave of symbols and associations. I can feel the narrative tension rising in me like a tide, feel the undertow of the happy ending that will never come to be, and feel the lingering sweep of a good book’s afterglow that bathes my reality in its refractive light for hours after I have finished reading. And so a lack of visual imagery doesn’t feel to me like a weakened experience of the scenes cast by fiction, because the dark matter of my own memories has the same tone and texture…”

These words provide us with some insight as to how she reads: it’s the emotional charge of a literary text, the intensifying and abating of tension, the sway and steadiness of human connection—it’s these, along with the associations they evoke in her conceptual mind, that make her feel immersed. From what I understand (and I could be wrong), the immersion happens from within. It doesn’t require a stimulation of the mental senses through verbal cues, because the one thing needing stimulation is the heart, and the one thing that ought to be teased is curiosity. The aphant’s mind actively looks for concepts while processing emotion—a task not difficult for them, for that is how they think, remember, and reason. That is their brain’s natural setting.

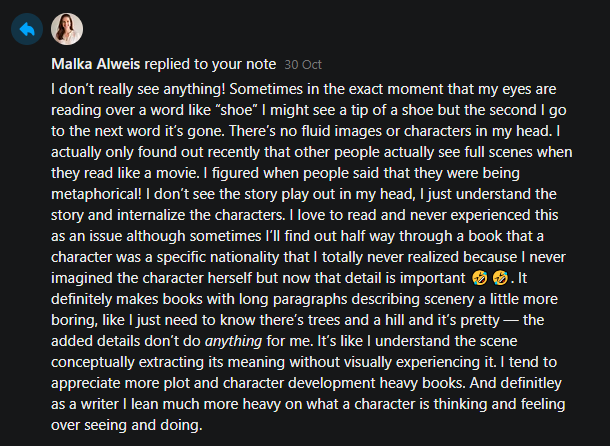

In October, I had a brief but intriguing interaction with aphantasic reader and writer Malka Alweis, writer of the publication Mom-Colored Glasses. She kindly shared what her experience with books is like, and I’ve found it aligns with what Dr. Deer has written:

Alweis segues right into the second question I posed earlier: can aphants be fiction writers?

Indeed they can. And they can be mighty good ones.

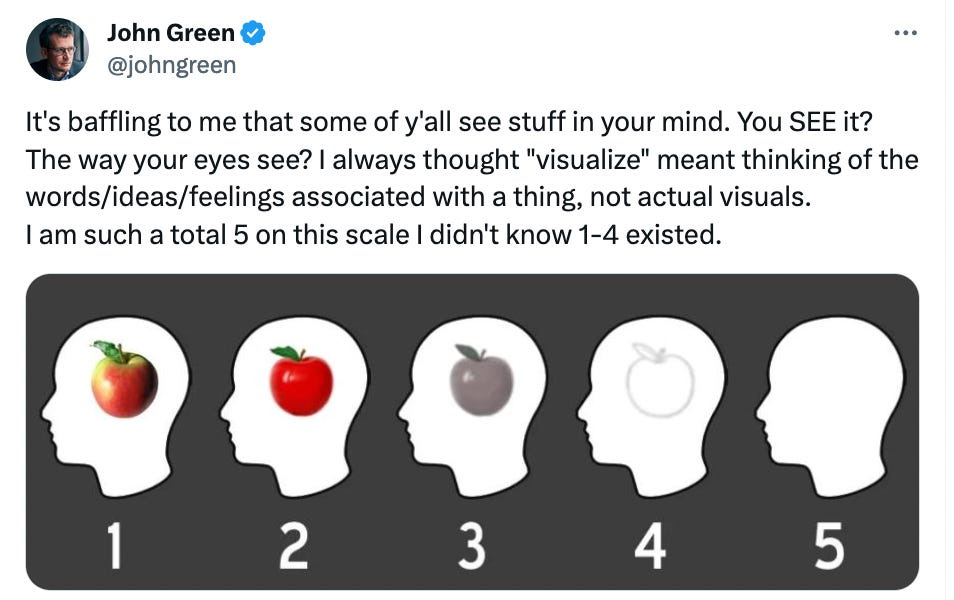

Two years ago, novelist John Green publicly expressed his shock at finding out visualization is an innate skill most people have.

I haven’t personally read any of his books, but I checked a few online reactions from his readers and it seems the revelation didn’t surprise them much. Someone commented that Green’s writing style feels more like “thoughts and emotions described in language” than a “movie in the mind.” Phantasics looking for “scenic” fiction might find his writing sparse, seeing it doesn’t “demand a mind’s eye,” what with there being less explicit imagery (John Green readers: I’d love your opinions!).

So does this mean phantasic writers can’t write visually evocative narratives?

We’ve seen how diverse the (a)phantasic spectrum is: not one person’s inner world is like the other’s. Following that logic, I’m inclined to say that not one’s ability to express that world is like the other’s, either.

In an article for The Guardian, fantasy novelist Mark Lawrence—also an aphant—claims he’s never had an issue with writing vivid prose:

“I write books that are often praised for clear and evocative visual description. I’m asked by people if I’ve climbed rock faces, fought with swords or even had cancer, because my descriptions of these experiences have convinced people who have actually lived them that I must have, too. (I haven’t.)”

Me? I find this fascinating.

First we have Alweis, who prefers to communicate what a character thinks and feels instead of what he/she sees and does. We have Green, too, whose writing is said to be “fine for aphantasics” for not lingering on visual elements. But then as a contradiction comes Lawrence’s comment.

I think the whole of phantasia can be brought down to this one word, actually: contradiction.

Amid the many uncertainties, however, one thing remains true: aphantasia is not an impairment of the imagination. It is not an impairment—period.

It is, in fact, with all its contradictions, a perfect illustration of the imagination: of how vast, how unique, how beautiful it can be.

Each (a)phantasic variation is a variation of human creativity.

Mark Lawrence has expressed something in his article that’ll linger in my mind for long:

“I suspect that we have much to learn about quite how unique each of us is in the handcrafted virtual reality we all maintain behind our eyes.”

Yes, we do.

The study of mental imagery may still be in its early days, but already it has kindled much awe and appreciation for the puzzling, beautiful mess that is the imagination.

I’d love to know about yours.

How vivid is your inner world, and how does it affect your practice and enjoyment of storytelling?

Until next time,

Heba

Feel free to share your experiences in the comment section:

Know someone who might appreciate learning about aphantasia? Make sure to share this with them:

What is Aphantasia? (Aphantasia Network ©)

Impact of Aphantasia on the Reading Experience (Aphantasia Network ©)

This was so fascinating! Mark Lawrence is an aphant?? I read The Book That Wouldn't Burn (one of his books) and I was IMMERSED. I was genuinely sucked in and loved the whole experience.

I took the aphantasia test and it said I was phantastic, but I lean more toward aphantasia on the scale, which I think makes sense because my visualization isn't incredibly vivid.

Oh my gosh! I felt so seen in this essay of yours, Heba. People rarely talk about aphantasia, and for you to talk about aphantasia for writers and readers made me sooo excited! I have aphantasia (I scored a 23), but I have loved writing fiction, reading fiction, and drawing (my only 3 hobbies 🥹) since I was veryyy little, even before I realised my lack of visual imagery.

My love for fiction literature and art as a whole, despite people thinking we require vivid imagination, has never dwindled. And anyway, I do imagine! Just not in the same way most do. My imagination is series of events, dialogues, character interactions, dynanmics or symbolism and metaphors I find interesting. Just without the faces. Or colors. Or visuals at all, haha.

Your essay was was an incredible love letter for people with aphantasia, it was incredibly accurate and relatable, and I have genuinely never felt more seen in this area ever! I appreciate this article so much, thank you 🫶