The LOTR Reading Diaries: Book One, 'The Fellowship of the Ring'

Reviewing chapters 1-12 as a first-time reader

Three Rings for the Elven-kings under the sky,

Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone,

Nine for Mortal Men doomed to die,

One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne

In the Land of Mordor where the shadows lie.

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them

In the Land of Mordor where the shadows lie.

I firmly believe that every book finds us at the right time, and when it does, it has just the right thing to offer.

The Fellowship of the Ring had been on my shelf for over a year until I picked it up three weeks ago. I don’t know what kept me from doing so sooner; whenever I wanted to choose my next read, my eyes regarded it longingly but my mind went: not yet.

My first exposure to Tolkien was through his famous essay, On Fairy-Stories, which I discovered back in April. It’s academic in nature—densely so in certain parts. But it’s the most passion-charged academic work I’ve come across. Tolkien presents a fervent defense of fantasy, particularly those stories taking place within the realm Faërie (stories known as fairy tales). Once he’s done arguing for their literary legitimacy, he moves on to persuade the reader that while children benefit from fairy tales, it is the adults who need them most. I loved this essay so much I wrote a review, which you can access below.

Almost two months later, I saw a Note recommending Leaf By Niggle—arguably his most underrated work of fiction. But it’s one of his most profound, and that profoundness stems from the fact that the story is quite personal.

I see Tolkien as belonging to a rare breed of authors because he actively voiced his struggles with the craft. He didn’t shy away from admitting his shortcomings. He didn’t frame writing as something effortless. No—he acknowledged his victimhood to the obstacles faced by the common writer, humanizing the writing process. Leaf By Niggle captures his experience through the character of a painter—an obsessive, perfectionist, procrastinating painter—which is quite fitting because, while composing The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien was an obsessive, perfectionist, procrastinating writer.

This story I’ve discussed in another essay, featuring the lessons we can learn from Niggle (and, by extension, Tolkien) as people with creative pursuits.

With that said now, I think I understand why I kept putting off The Fellowship of the Ring. Had I started it right away, having read neither the essay nor the short story, I wouldn’t have held the same appreciation for it as I do now. I wouldn’t have known just how much fantasy meant to Tolkien. I wouldn’t have known what great pains he took to compose this masterpiece of a narrative—that he faced constant self-doubt, thought it unpublishable, and spent a decade perfecting every little detail in worldbuilding, plot, and characterization. I needed to be let into the mind of the author before witnessing its creation.

It found me at the right time.

What it has offered me to date is a memorable adventure, and it’s far from over. Having now reached the halfway point, I think there’s no better way to celebrate it than by documenting my experience. That’s what this post is: the first part of a series in which I review The Lord of the Rings, Book by Book1, as I progress in the story.

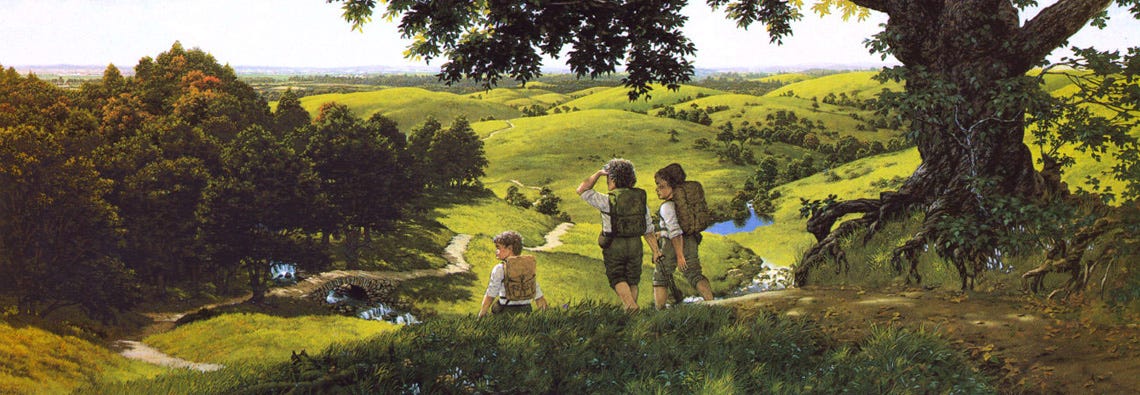

Chapters one to twelve cover Bilbo’s departure from Bag End, Frodo’s subsequent journey through the Shire, up until the chase at the Ford of Bruinen. A good deal happens on the way, with much learned and many met. At this point, I hardly know what to expect from the coming chapters, but I’m happy to share what I think and feel so far.

Concerning hobbits, the Shire, and the finding of the Ring

Hobbits are an unobtrusive but very ancient people, more numerous formerly than they are today; for they love peace and quiet and good tilled earth: a well-ordered and well-farmed countryside was their favorite haunt. They do not and did not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge-bellows, a water-mill, or a hand-loom, though they were skilful with tools. Even in ancient days they were, as a rule, shy of ‘the Big Folk’, as they call us, and now they avoid us with dismay and are becoming hard to find. They are quick of hearing and sharp-eyed, and though they are inclined to be fat and do not hurry unnecessarily, they are nonetheless nimble and deft in their movements.

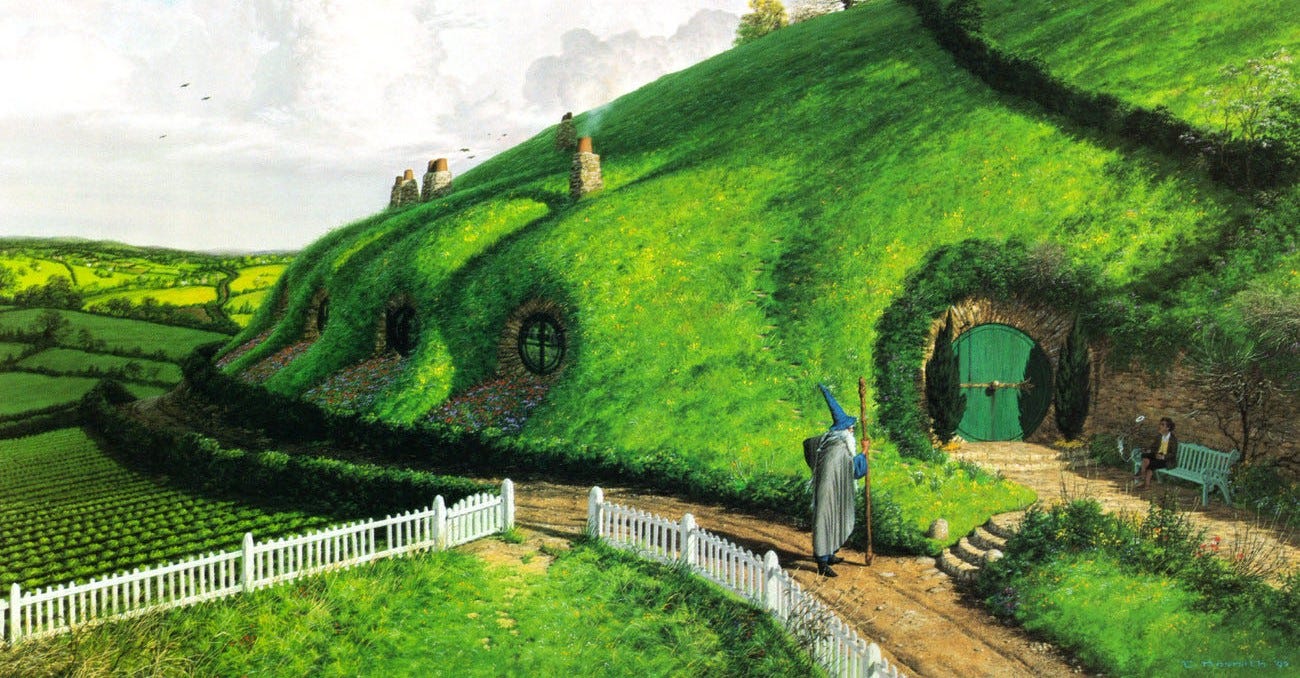

Ah, to be a hobbit—to live in a hobbit-hole with its round door and round windows, tending a well-kempt garden every day, and avoiding humans all the way…

The stage is set with a prologue, in which we learn what hobbits are and how many types of them exist. It’s not a mere profile description; what Tolkien relates appears to be part of an intricate fictional history. In fact, what makes LOTR different from other fantasy stories I’ve read is that nothing is treated as new. The protagonist is not someone who has stumbled upon a magical world about which they have to learn from scratch. Instead, the main character is a native, and has been in that world for thirty-three years when the narrative opens. Frodo is thus already aware of what constitutes life in the Shire; he knows much of its history, its different regions, and what roams in them. The reader’s role is to follow the conventions—to accept what has been for centuries established, to grow more familiar as they read, and to discover that which Frodo discovers along the way.

In other words, reading The Fellowship feels like traveling to a foreign country that speaks a foreign tongue: nothing is understandable at first, but the more you mingle and learn, the more you come to appreciate the richness of its culture.

Speaking of tongues—I’ll allow myself a small diversion from the topic to mention something that’s been on my mind since starting the book: the fact that Tolkien invented a language specific to Elves baffles me. Or languages; what I’ve read doesn’t yet mention if more than one exists. By chapter twelve, there’s not much of the language except for the inscription on the Ring and a few words exchanged between Strider and Glorfindel. Still—that the author has gone to such lengths only speaks to his masterful worldbuilding skills and commitment to quality storytelling. Inventing a language—one that is both functional and efficient—is no simple feat; very few people are recognized as having created fully developed languages that are usable for everyday interaction or narrative immersion. Also, I think it becomes even more of a challenge when you’re inventing one for nonhuman creatures, because you’d have to come up with pronunciations, intonations, and structures that fit the nature of those creatures. For example, trolls and elves should not speak similarly. In my head the words of a troll are cacophonous, an elf’s softer (but that might be a stereotype on my part). It comes down to the fact that language is not just a means for communication, but also an identity marker. The language you ascribe to some creature should thus be true to the identity you create for it. I’m excited to see what Tolkien has done for this aspect of his narrative.

Back to the prologue—the good thing is that it does not overwhelm the reader with information. It’s not exactly short, but it’s kept simple. Not too much is revealed at once, but by the time the story starts, the reader feels equipped with the necessary context to comprehend the significance of Frodo’s quest and what exactly is at stake.

The story of how Bilbo obtained the Ring is where most of my questions are. Bilbo is described, in the prologue and the narrative, as an honest, good hobbit, but the fact that he fabricated an alternate version of that story tells me there’s more to him than we know. Then there’s his departure in the first chapter. He may have framed it as a kind of holiday he’d been seeking as an aging hobbit, but I can’t help suspecting he was not entirely honest here as well.

When Frodo discovers where Bilbo has gone, I am almost certain he’ll also be discovering a side to him he doesn’t know. I don’t want to believe it, but I do wonder if it’ll be an unpleasant side.

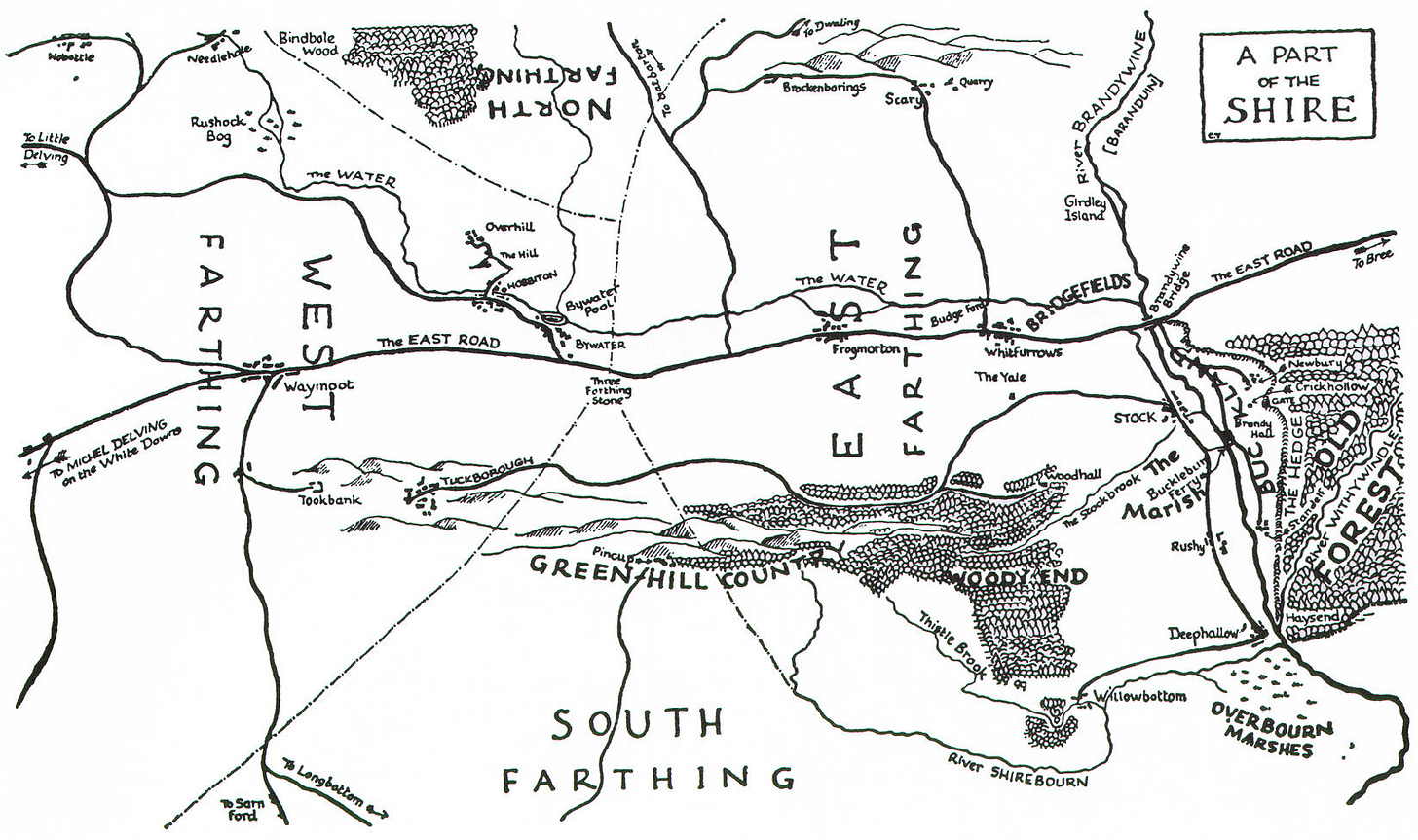

After the prologue comes a map showing a part of the Shire, which I turned back to every time the four traveling hobbits made progress in their journey.

Because so much happens across the first twelve chapters (and because discussing all of my opinions will probably render this post a 1+ hour read), I will be summarizing in the next sections what has stood out to me the most.

The monomyth: adventure comes knocking on Frodo’s door (literally)

One of the first things I noticed while reading is how closely the plot follows Joseph Campbell’s famous storytelling template, The Hero’s Journey or The Monomyth. It is summarized in three acts (you can read more about it here):

Separation: the protagonist would be leading an ordinary life before something (or someone) disrupts their routine, inviting them to begin a quest of some sort. The hero would hesitate or resist, but eventually, after meeting a wise mentor who helps prepare them for the journey, they would depart.

We can see how The Fellowship parallels this: seventeen years after Bilbo’s departure, Frodo is minding his business when Gandalf the Grey shows up and informs him of the danger the Ring carries. Gandalf embodies the wise mentor, advising the hero on when to leave and what route to take to his destination. Frodo hesitates and resists—“I’m not made for perilous quests. I wish I had never seen the Ring!”—and while Gandalf urges him to leave as soon as possible, he postpones it a few months, during which he makes arrangements, before at last leaving on September 23rd—the same date on which Bilbo left all those years ago.

Alan Lee’s Frodo and Gandalf Initiation: this is where the hero undergoes several trials and meets other characters, who may be allies or enemies, on their way to fulfill the quest. As they draw closer, there is usually a crucial, life-threatening event. This ordeal is overcome, and the hero is rewarded with treasure, power, or insight.

The first trial Frodo’s lot undergoes is learning that they are being chased by the Black Riders, and as they move they find themselves in several sticky situations: being ensnared by Old Man Willow, captured by the Barrow-wights, almost getting discovered at the Prancing Pony, Frodo being wounded by a Black Rider at Weathertop, then the climactic chase at the Ford. And as they pass these trials, several new characters are introduced, including allies (Fatty Bolger, Tom Bombadil and Goldberry, Strider, Glorfindel) and enemies (The Black Riders, Old Man Willow, Bill Ferny). I’ll have to keep reading to find out how the rest of the story aligns to (and whether it deviates at all from) Campbell’s template.

Return: this latter part of the story consists of the hero making the journey back home. In most cases, they are chased or challenged again, which allows them to be “reborn” or changed in one way or another. They at last make it back to their ordinary life, bringing knowledge, healing, or benefit to their people.

I can’t be sure if Frodo will be successful in his adventure. In chapter five, A Conspiracy Unmasked, he has a vivid dream that I’ve kept in mind since first reading it:

[…] Eventually he fell into a vague dream, in which he seemed to be looking out of a high window over a dark sea of tangled trees. Down below among the roots there was the sound of creatures crawling and snuffling. He felt sure they would smell him out sooner or later.

Then he heard a noise in the distance. At first he thought it was a great wind coming over the leaves of the forest. Then he knew that it was not leaves, but the sound of the Sea far-off; a sound he had never heard in waking life, though it had often troubled his dreams. There were no trees after all. He was on a dark heath, and there was a strange salt smell in the air. Looking up he saw before him a tall white tower, standing alone on a high ridge. A great desire came over him to climb the tower and see the Sea. He started to struggle up the ridge towards the tower: but suddenly a light came in the sky, and there was a noise of thunder.

I’m almost certain this dream is symbolic, perhaps even foreshadowing. I can think of two interpretations:

The Sea symbolizes Frodo’s success in his quest, and the white tower is a stand-in for Gandalf. At this point in the story, Frodo doesn’t know where his mentor is and whether he is alright, having not seen nor heard from him since before the adventure. That the white tower is situated between dream-Frodo and the Sea is representative of how Gandalf stands in between real-Frodo and the task at hand: the wizard is the means through which the hobbit can achieve success, just as the white tower is the means through which he can see the Sea. The thunder that interrupts dream-Frodo’s climb may be symbolic of an interruption that has seized Gandalf away and separated him from the hobbit. Given the nature of thunder, it’s likely that this interruption is of a dangerous kind—and that Gandalf is probably at risk.

The second possible interpretation is that the white tower represents Frodo’s peace—a peace that can only be realized once the quest is accomplished. The thunder again symbolizes an interruption, but not one that entails separation; this one entails failure. Frodo might not succeed at his task, and darkness will take over the land just as it did over the view surrounding the tower.

Of course, I might be wrong, and this dream could be nothing but an allusion to the second LOTR instalment: The Two Towers. The prologue mentions a Dark Tower, and this dream mentions a white one. Still, dream interpretation is one fun way I like to engage with stories, especially fantasy.

Sam Gamgee is the most precious character and I’m scared for him

It’s hard not to love Sam Gamgee—not when he’s introduced as a clumsy, elf-loving hobbit. In chapter two, The Shadow of the Past, Gandalf is confiding in Frodo what he knows about the Ring and the quest to be undertaken. It’s a conversation that would’ve interested any passerby, what with the mention of Sauron and Mordor. But not Sam. His role as Frodo’s gardener gave him the perfect opportunity to overhear all which Gandalf had to say from start to finish. But no—Sam only stopped to listen when his sharp ears caught the word Elves.

“Get up, Sam!” said Gandalf. “I have thought of something better than that. Something to shut your mouth, and punish you properly for listening. You shall go away with Mr. Frodo!”

“Me, sir!” cried Sam, springing up like a dog invited for a walk. “Me go and see Elves and all! Hooray!” he shouted, and then burst into tears.

At a first glance, Sam is this innocent sidekick who hasn’t fully grasped the gravity of the situation. He’s in it for the Elves. I half expected him to cower back to Bag End after fulfilling this one goal (and fulfill it he does), but he instead reveals a side to him that surprises both Frodo and me; he musters up remarkable courage and a clear understanding of what risks comprise Frodo’s task. Sitting for breakfast the morning after the hobbits’ encounter with Gildor and his group of High Elves, this conversation unravels:

“Well, Sam!” said Frodo. “What about it? I am leaving the Shire as soon as ever I can—in fact I have made up my mind now not even to wait a day at Crickhollow, if it can be helped.”

“Very good, sir!”

“You still mean to come with me?”

“I do.”

“It is going to be very dangerous, Sam. It is already dangerous. Most likely neither of us will come back.”

“If you don’t come back, sir, then I shan’t, that’s certain,” said Sam. “Don’t you leave him! they said to me. Leave him! I said. I never mean to. I am going with him, if he climbs to the Moon; and if any of those Black Riders try to stop him, they’ll have Sam Gamgee to reckon with, I said. They laughed.”

“Who are they, and what are you talking about?”

“The Elves, sir.”

[…]

“Do you feel any need to leave the Shire now—now that your wish to see them has come true already?” asked Frodo.

“Yes, sir. I don’t know how to say it, but after last night I feel different. I seem to see ahead, in a kind of way. I know we are going to take a very long road, into darkness; but I know I can’t turn back. It isn’t to see Elves now, nor dragons, nor mountains, that I want: but I have something to do before the end, and it lies ahead, not in the Shire. I must see it through, sir, if you understand me.”

Sam’s vagueness is concerning. It’s unclear whether he knows what this “something to do” is. But, from my experience with other stories, whenever a likeable character decides that they have to stick around, it’s usually because they will be a crutch for the protagonist, helping them overcome some great danger—and usually at the cost of the sidekick. In other words, the sidekick will be sacrificed for the hero’s sake.

I sincerely hope that is not the case.

But as I read on, I began to find certain patterns in Sam’s behavior that might confirm my fears. Among the three accompanying hobbits, he is the one most fiercely loyal to Frodo. It shows in every chapter. He chokes with tears when Frodo gets injured by the Riders. And before the Black Riders appear at the Ford in chapter twelve, Sam shows a clear distrust of Glorfindel—despite his being a friend of Strider’s and an Elf—when the latter suggests that a wounded Frodo be ridden away, alone, on his white horse. And then there’s the little moments, like when Pippin intended to eat all the bread during breakfast but Sam insisted he save some for Frodo.

He refers to him as “sir,” but not just because he works as his gardener. If that was the case, he would’ve dropped this formality as soon as they left Bag End. What I believe is that Sam genuinely admires Frodo and looks up to him. It’s a relationship that goes beyond mere liking of the other.

Something else I’ve noticed about Sam is a fierceness of character that the other hobbits don’t seem to possess. There’s a fire in him that’s lit up at the slightest provocation; he reacts to confrontation with no fear or hesitation. One instance I recall is when Bill Ferny scorns Strider and the hobbits as they leave Bree:

“Morning, my little friends!” said Ferny. “I suppose you know who you’ve taken up with? That’s Stick-at-naught Strider, that is! Though I’ve heard other names not so pretty. Watch out tonight! And you, Sammie, don’t go ill-treating my poor old pony! Pah!” He spat again.

Sam turned quickly. “And you, Ferny,” he said, “put your ugly face out of sight, or it will get hurt.” With a sudden flick, quick as lightning, an apple left his hand and hit Bill square on the nose. He ducked too late, and curses came from behind the hedge. “Waste of a good apple,” said Sam regretfully, and strode on.

Okay—he’s cool. And funny even when he’s not trying. But—and this could be my anxiety speaking—impulsiveness and fierce loyalty can be a dangerous combination. I can think of a variety of scenarios in which Sam would spring up to Frodo’s (or someone else’s) defense without thinking of the consequences. And it worries me.

And then this line shows up later on, after Sam finishes reciting a funny poem:

“I am learning a lot about Sam Gamgee in this journey,” said Frodo. “First he was a conspirator, now he’s a jester. He’ll end up by becoming a wizard—or a warrior!”

“I hope not,” said Sam. “I don’t want to be neither!”

Do I think this is foreshadowing something? Yes. Sam as a warrior isn’t unimaginable. In many ways, he already is one.

Everything is uncertain now. All I know is Sam Gamgee is the most precious character and his fate is something I’m keeping an eye out for.

What’s up with Tom Bombadil?

One can’t speak of whimsy without speaking of Bombadil. He shows up in the Old Forest, donning a blue coat and yellow boots, singing something nonsensical. He’s a character full of contradictions: seems ancient, but acts childlike; looks powerless, but possesses strange control over the natural elements in his area. He is one and constantly moving, yet can be summoned as easily as though someone cried Accio, Bombadil!

And most significant of all: he is unaffected by the Ring.

Tom Bombadil doesn’t disappear when he puts it on. He doesn’t feel tempted by it. He doesn’t grow attached. I can only wonder: what kind of power must someone have to resist something even Gandalf fears?

I’ve also wondered why Gandalf didn’t employ him for the task. But then, as I re-read the chapters in which he is featured, I noticed something interesting he says: that he has no desire to leave his land and involve himself in wider affairs. It’s got me thinking that maybe Tom’s powers are only functional within the boundaries of his land. Supposing this is true, then the why is as big a mystery to me as is Tom himself.

The Ford is a point of escalation

Chapter twelve, Flight to the Ford, is special in many ways. One such way is that it introduces a new character, Glorfindel, with a beautiful description:

The light faded, and the leaves on the bushes rustled softly. Clearer and nearer now the bells jingled, and clippety-clip came the quick trotting feet. Suddenly into view below came a white horse, gleaming in the shadows, running swiftly. In the dusk its headstall flickered and flashed, as if it were studded with gems like living stars. The rider’s cloak streamed behind him, and his hood was thrown back; his golden hair flowed shimmering in the wind of his speed. To Frodo it appeared that a white light was shining through the form and raiment of the rider, as if through a thin veil.

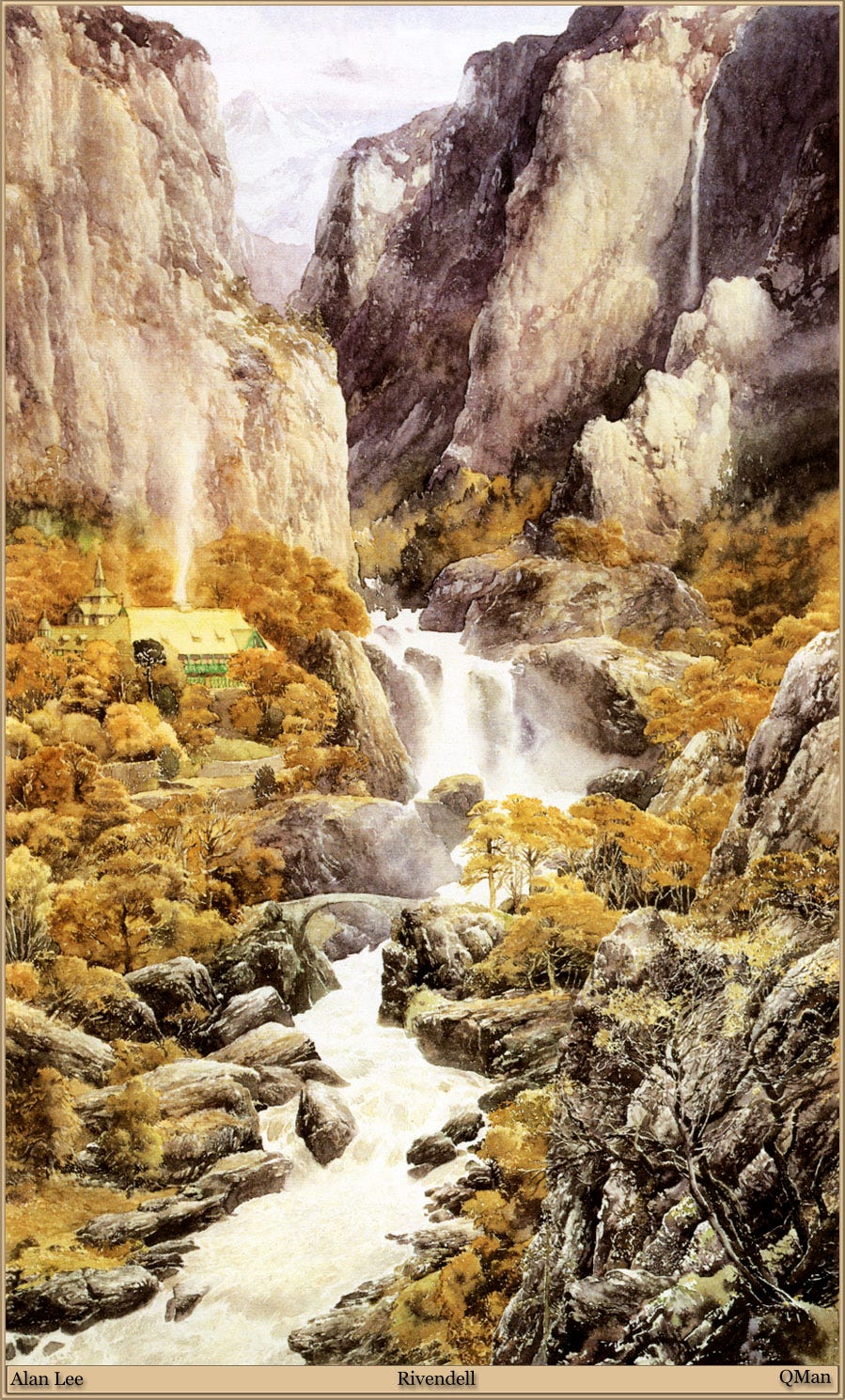

Glorfindel arrives at just the right moment, uplifting the depressed spirits of the travelers. We witness a nice reunion between him and Strider, who a few pages prior informs the hobbits he’d once lived in the peaceful land of Rivendell. Its ruler, Elrond, is described as venerable, as mighty among Elves and Men. Rivendell has been a sanctuary for the weary and oppressed for as long as most Elves can remember.

And it’s this fact that I want to focus on.

I think the arrival of Strider and the hobbits at Rivendell represents a major escalation. At this point, we don’t fully understand what happened at the Ford; Frodo loses consciousness as soon as the Riders are eliminated. It’s unclear if it was the water that drowned them, or Glorfindel who attacked them (for Frodo recalls seeing a “white light” approach the Riders from behind). Regardless, the fact that Sauron’s servants were intimidated in this land makes it plausible that Rivendell will see dark days soon—that its Elves will be targeted for the help they’ve offered Frodo—and the longer Frodo stays there, the more likely it is that this happens.

I believe this episode is what will mark the start of Elvish involvement in Frodo’s quest. Perhaps Glorfindel (or another Elf; maybe one more equipped for battle) will be asked to accompany the group to Mordor.

With the next chapter being titled Many Meetings, I hope a certain reunion takes place—that of Frodo and Gandalf’s—that the hobbits meet Elrond and, if my theory above is correct, that some new Elf accompany them on the rest of their journey.

Memorable quotes from Book One

I thought I’d dedicate the last section of this post to a list of my favorite Book One passages. In addition to the aforementioned Glorfindel introduction, it includes:

“Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. For even the very wise cannot see all ends.” —Gandalf

“Courage is found in unlikely places.” —Gildor

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

The night was railing against the morning of which it was bereaved, and the cold was cursing the warmth for which it hungered. (This is part of the narration. I thought the line was so beautifully written that I had to feature it).

This wraps up the first part of the series (thank you for reading until the end!). I’ll be reading Book Two over the next few days, readying the concluding post for The Fellowship of the Ring.

I’m loving it so far, and there’s so much that can happen. Whether my little theories in this post are true I’ll be finding out soon; I’m excited and worried and psyched and scared all at once. But above all, I’m grateful that I have this small community with whom I can share and discuss this reading experience.

Until next time,

Heba

By “Book” I am referring to the parts in each title. The Fellowship of the Ring, for example, is divided into two Books.

I have enjoyed reading your post and look forward to reading your next one.

I have read Lord of the Rings many times over the years.

The Hobbit will tell you more about Bilbo Baggins and cover the finding of the ring. It was originally only intended as a story JRR Tolkien told to his children.

I have also read The Silmarillion, which covers the first age of Middle Earth (focusing on the Elves).

The Histor of Middle Earth series is interesting where Christopher Tolkien covers the history of the development of his father's legendarium, including the creation of the elvish languages.

What a feat! I have also always wanted to read Tolkien, but the timing has never been right.