Are You a Niggle?

J.R.R. Tolkien's underrated short story as an allegory of the creative process

Writing is hard.

If it’s not crippling self-doubt that has paralyzed my hands over the keyboard, it’s writer’s block—that unwelcome feeling of being an obstacle to your own work. Sometimes I’m stuck at a crucial point in the plot; other times I’m failing at the seemingly simple task of articulating a thought.

Then there’s the whole struggle with time. That desperate search for the elusive “enough time,” or even the nonexistent “right time” to write.

My consolation is that I’m not alone. God knows how useful a space Substack has been for writers to air such grievances. There’s also the fact that these struggles are not a guarantee of failure—even the literary greats have complained.

It is well-documented that J.R.R. Tolkien worried a lot about not finishing The Lord of the Rings. It took him over a decade to complete the manuscript (from 1937 to 1949). During this period, he sent his son letters expressing his frustration with the complexity of the story and his fear that it would never see the light of day.

In separate letters written in 1945, Tolkien said:

“I am dreading the next batch of ‘The Lord’—it is growing too large, and I begin to feel it’s becoming unpublishable.”

“I now wish that I had never begun it, and I fear I shall never end it.”

—The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (edited by Humphrey Carpenter)

That same year, the Dublin Review published his short story titled Leaf By Niggle. He has spoken of it as something that was revealed to him in a dream, as he woke up one day with the idea pretty much complete in his head. It took him only a few hours to write down and edit, whereas he normally composed “only with great difficulty and endless rewriting.” (from a letter to Stanley Unwin; March 1945).

What makes Leaf By Niggle stand out to me (in addition to its whimsical title) is the fact that it was born out of this anxiety over LOTR:

“[…] it arose from my own preoccupation with The Lord of the Rings, the knowledge that it would be finished in great detail or not at all, and the fear (near certainty) that it would be ‘not at all’.” (from a letter to Caroline Everett; June 1957).

Although Tolkien often expressed his dislike of allegory, this short story is just that. Two interpretations seem to be most popular:

That it is an allegory of life and death as understood in his Christian faith.

That it is an allegory of the creative process—an illustration, through the character Niggle, of the difficulties Tolkien faced in his writing.

I read a Note on here not long ago saying how amazing it is that writing is so personal an experience and yet, in many ways, also so universal. Tolkien may have thought his struggles were personal, but when creative people today read Niggle, they find that it speaks to them. It does to me.

Today’s post identifies the struggles represented in the story and frames them as little lessons we can apply to our work. As you read them, do reflect on how they relate to your own writing habits and ask yourself: am I a Niggle?

Note: a downloadable PDF version of the short story is linked here. If unable to read it, you may refer to the summary below

Niggle’s story, in brief

Niggle is a little man who has a long journey to embark on, but he doesn’t feel ready for it. He is a painter, but not a very successful one because there are many other things for him to do besides painting. Nuisances, he calls them. The laws of his country are strict, requiring its people to complete a variety of practical tasks for which they will be held accountable. And as if that’s not enough, he’s got a needy neighbor with a lame leg constantly dropping in for help with some errands. Niggle blames his kind heart for his inability to paint as he likes; he has the desire to deny Mr. Parish (and other people) his help, but nearly always finds himself unable to do so. He grumbles, curses, and spirals into a very bad mood—but he often does what he’s asked.

At other times, he doesn’t paint simply because he’s idle.

When the story opens, Niggle is working on a vast canvas: a picture of a huge tree with a background of forest and mountains. It’s his most ambitious work yet, with intricate, realistic detail, and while he’s obsessed with the idea of finishing it, he worries he won’t before the time for the unavoidable journey arrives.

Mr. Parish interrupts Niggle’s painting one day, desperate for help. The wind has blown his roof off, causing his house to flood and his wife to fall sick. Without so much as glancing at the painting, he begs Niggle to fetch him builders and a doctor from the city. Niggle hesitates. But because of his kind heart, he gives in.

It rains there and Niggle comes down with a cold. His sickness renders him unable to paint for several days. Meanwhile, the builders fail to show up at Mr. Parish’s, but his wife gradually recovers.

Just when Niggle starts to feel well enough to paint, someone else interrupts him: an Inspector of Houses arrives to criticize him for not helping his neighbor with the roof. Niggle justifies that he’d called for the builders but they didn’t show. The Inspector suggests that Niggle should have used the spare material in his possession to build Parish a new roof. When Niggle asks what material he’s referring to, the Inspector gestures at the painting.

Niggle doesn’t have time to argue, because a moment later someone called the Driver appears. He has come to take Niggle on his long-awaited journey. Niggle freaks out. He hasn’t packed, hasn’t made preparations. He’s allowed to prepare a small suitcase before being so abruptly taken.

His destination: a place called the Workhouse, where he is kept in a dark cell and ordered to perform hard physical labor for what feels like a century. One day, from within his cell, he overhears two Voices discussing the quality of his character. One Voice is harsh, criticizing Niggle for not properly serving his community; another is gentler, pointing out that even though he complained, Niggle did his best effort most of the time. The two Voices decide that Niggle is ready for the next stage.

He is released, taken into a faraway land where he encounters a bicycle with his name on it. He rides it down a path, then stops in shock: the place resembles, to a great extent, the picture he spent a good part of his life painting. The tree. The leaves. The mountains in the far background. He feels the urge to make it his living space, and sets out to build a cottage and garden. But he knows he needs Parish’s help, for Parish is a great gardener.

As if summoned, Parish arrives and the two work together. But days after the work is done, Niggle decides to leave the place to explore the mountains ahead—mountains he never really finished painting. Parish stays behind, waiting for his wife, with whom he intends to live in that cottage.

Back in the country, some of Niggle’s acquaintances are discussing him and his life’s work. A man by the name of Tompkins argues that Niggle’s painting was useless—a total waste of resources and of no benefit to society. Another, named Atkins, counters that. It is revealed that Niggle’s huge painting was eventually used to help rebuild roofs for people with destroyed homes. But Atkins managed to save one part of the painting—a leaf—which he took to the local museum for display. The artwork was called Leaf: by Niggle, but even that was destroyed when the museum burned down.

In the end, the two Voices at the Workhouse decide to make the peaceful location, where Parish and his wife are, the destination of everyone released from their hard labor. They name the location Niggle’s Parish.

A religious reading interprets Niggle’s unavoidable journey as death, emphasizing how unanticipated it can be and how little we prepare for it. The Workhouse thus becomes a purgatorial destination of some sort. Through isolation and physical labor—and, more importantly, through a forced interruption of his creative work—Niggle learns obedience and humility, expiating his sins before earning his release into a restful, beautiful place akin to a paradise. The longstanding subject of his imagination becomes his reward.

But if we were to merge the two aforementioned interpretations, I’d see the result as such: Niggle, as an artist, has committed in his lifetime a variety of creative sins that earn him a punishment most feared by all creatives alike—that of being prohibited from practicing his art, of being forcibly detached from his imagination and thrown into a rigid, practical reality. Once cleansed of such sins at the Workhouse, Niggle earns his freedom and the right to not only paint again but also inhabit his creations.

I explore below what these sins are and what we can learn from them as writers.

Creative sin #1: perfectionism

“He was the sort of painter who can paint leaves better than trees. He used to spend a long time on a single leaf, trying to catch its shape, and its sheen, and the glistening of dewdrops on its edges. Yet he wanted to paint a whole tree, with all of its leaves in the same style, and all of them different.” (Leaf By Niggle; page 2)

Niggle’s perfectionist tendencies are described early on in the story. It’s his habit to indulge in a single leaf for long stretches of time, trying to capture its essence and present it as realistically as possible. And just a paragraph later, we learn that he intends to perfect his work not only in its quality, but size, too:

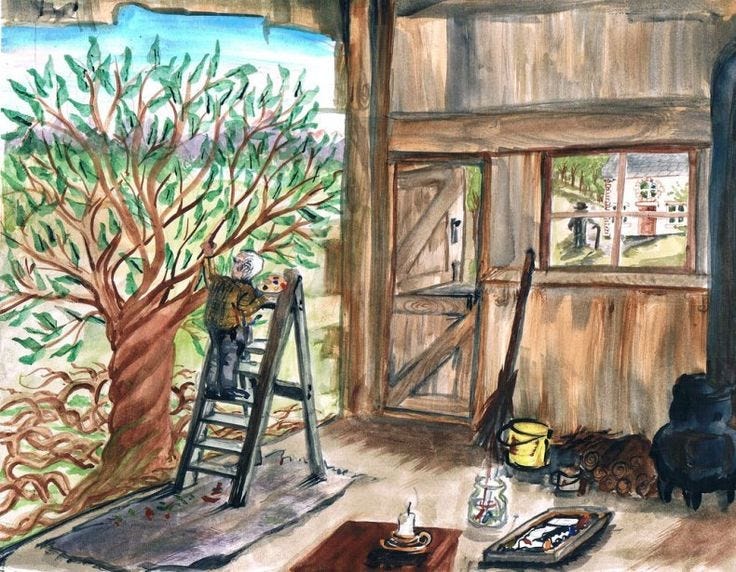

“It [the picture] had begun with a leaf caught in the wind, and it became a tree; and the tree grew, sending out innumerable branches, and thrusting out the most fantastic roots. Strange birds came and settled on the twigs and had to be attended to. Then all around the Tree, and behind it, a country began to open out; and there were glimpses of a forest marching over the land, and of mountains tipped with snow. […] Soon the canvas became so large that he had to get a ladder; and he ran up and down it, putting in a touch here, and rubbing out a patch there.” (page 2)

“The more, the merrier” doesn’t always apply to art. Niggle’s desire to paint every leaf in exquisite detail and depict an entire world behind it portrays a form of perfectionism that tries to do too much at once. While creating, it’s easy to get carried away and fall into the illusion that the more the piece contains and the more it represents, the more meaningful it is. But a lot can be said with little—little paint, little color.

And little description.

In a creative writing lecture I once sat for, the instructor repeatedly emphasized the power of minimalism and simplicity when it comes to description. If a writer wants to represent the horrors of war, for example, the mention of a baby’s bloodied shoe found in the rubble is often enough. One doesn’t need an account of everything seen and heard in the scene, for it’s the “small” things that tend to speak the loudest.

I think the same applies to plot and worldbuilding. A plot that is constantly interrupted by this and that subplot isn’t necessarily a strong one. Recently, I’ve been watching Brandon Sanderson’s series of writing lectures, and this is a point he underscores multiple times in one such videos: it can be tempting to divert the reader from the promise of the story for the sake of, say, character development, but subplots that don’t, or only slightly, contribute to the realization of that promise risk boring the reader and losing them. As for worldbuilding, especially in sci-fi or fantasy, a richly developed world doesn’t have to be overwhelmingly complex. Sure—readers enjoy complexity, but a good world is one that feels deep without becoming confusing. The challenge is to build with purpose, not just with excess.

Niggle’s relentless expansion of his Tree can thus be seen as symbolic of Tolkien’s tenacious perfectionism over Middle Earth. The fact that he described LOTR as becoming “too large” and “unpublishable” indicates he recognized the downside to being unnecessarily excessive and set out to work on it.

Creative sin #2: feeding obsession, lacking boundaries

Niggle embodies several symptoms of obsession over his painting. He can no longer think of his other pieces, left unfinished somewhere in his shed. Instead, he takes and attaches them to the edges of his big picture. He permits himself no other artistic outlet, exhausting his attention and creativity on that one project.

I have personally found that if I recruit all of my efforts for a single project, my creativity suffers. I begin to feel stuck. Worse—writing it starts to feel like a burden, as something I need to get out of my way. But when I distribute my energy across multiple creative activities, my interest in that project is reignited. I recharge by taking time off to sketch, read, or cook. The change eventually makes me miss the time I spend writing, and to writing I return with renewed purpose.

But other art, whether painting or something else, isn’t the only thing Niggle’s obsession deprives him of. It starts to disconnect him from other people, too.

“When people came to call, he seemed polite enough, though he fiddled a little with the pencils on his desk. He listened to what they said, but underneath he was thinking all the time about his big canvas, in the tall shed that had been built for it out in his garden (on a plot where once he had grown potatoes).” (page 2)

“He could not get rid of his kind heart. I wish I was more strong-minded! he sometimes said to himself, meaning that he wished other people’s troubles did not make him feel uncomfortable.” (page 2)

It’s an example of what I call a compromised art-life balance. Art isn’t work. It’s an escape from it, a way to feel alive again after hours of labor have numbed the body and mind down. And because art isn’t work, it’s not supposed to act like it, either. With that said, it isn’t meant to come at the cost of personal wellbeing: Niggle doesn’t just build the painting shed on top of his potato patch—he also abandons his gardening, sacrificing a source of provision. And art isn’t supposed to detach us (or even make us want to be detached), physically and/or emotionally, from the world around us, from people who care enough to check in.

But although we ought to let people in, it should be done carefully by establishing certain boundaries. Niggle acknowledges his weakness in this matter:

“There were many things that he had not the face to say no to, whether he thought them duties or not; and there were things he was compelled to do, whatever he thought.” (page 3)

By not establishing boundaries—by not knowing how and when to say no to things or people who try using up his time—he fails to make his art deserving of respect. It’s evident in the way Mr. Parish offers no word of support (not even a proper look at the painting) even though he finds Niggle at this task most of the time. Similarly, the Inspector wouldn’t have asked the canvas to be used for roof-building had he perceived it as something serious.

This doesn’t mean we have to push people away all the time. It means that when we become serious about our writing/art, we can make others understand its importance (to us and in general) by remaining reasonably steadfast in practice. It’s how we overcome guilt for excusing ourselves from some social occasions while simultaneously earning others’ understanding and respect for our time.

This is actually the only regard in which I’ll allow myself to compare art to work: if it is socially acceptable to deny other people favors or company because we’ve got work to do, then it should be as acceptable to do so for the sake of our art or writing.

Niggle speaks for Tolkien when expressing these frustrations. The author has multiple times written in his letters about social obligations that demanded his time and attention, but which he had to turn his back to for the sake of his writing.

The verdict: create a suitable art-life balance that offers you the pleasure of social interaction but not at the cost of your consistency in creative pursuits.

Creative sin #3: procrastination

I think procrastination is a culmination of the two previous sins: we allow people or things to take up our time so we can postpone the anxiety that comes with perfectionism. Procrastinating isn’t always about not being in the mood for our art; sometimes it’s just about avoiding a self-imposed pressure to impress—ourselves or some nonexistent audience.

But at other times procrastination comes from our belief that we will always have time to work on our projects. Niggle wishes he could say no to people, but he also admits to not feeling all that much perturbed by his inability simply because he’s certain he’ll finish the painting before his journey, no matter what.

But he doesn’t.

One can understand why Tolkien thought death was more imminent than his completion of The Lord of the Rings: WWII was rampant in the years he worked on it. But we don’t need to wait for the threat of death and destruction to start taking our craft seriously, for there is a number of other things that can cause just as sudden and (sometimes) irreversible interruption: unexpected long-term responsibilities, accidents, illness.

It’s why I think believing we’ll always have time is a foolish thing to do.

Niggle was humbled, but we don’t have to be.

Tolkien spoke for many of us by writing Niggle’s story. Thankfully, we don’t need to head to a Workhouse to cleanse ourselves of those creative sins, yet regardless of how we choose to do it, it will take a good deal of effort and patience.

And when we have as big a name as J.R.R. Tolkien sharing in our struggles, how can we not be encouraged?

Writing is a journey. Take down those obstacles one at a time.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post!

What are your thoughts on Leaf By Niggle? Do you interpret it in a different way? Feel free to share your thoughts with me.

And don’t forget to share this with someone you think will like it!

Until next time,

Heba

I really loved the phrase "art-life balance". A seasoned professional once told me: " In corporate there's no work-life balance; instead, there's work life harmony" to comment on the fact that work will always get into the way, but we just ought to make things happen.

Thanks for sharing Brandon's lectures. Do you mind sharing some resources you utilize to hone your craft? Your style is gripping in a unique way. ☺️

I see myself in the creative sins you have shared here. I have also been thinking a lot lately about what it takes to have a memorable piece of work out created. Yes, we battle through these creative sins and manage to get ourselves out of them or sometimes continue struggling through them without ever realizing it. Then we (I) find ourselves (my) asking should I wait for the spark that always ignites my writing, or I need to find away of learning to overcome what draws me back in my writing. Heba, what are your thoughts on being able to create memorable pieces of work.