The Modern Human Needs to Fast

In a world driven by instant gratification, fasting comes as a necessary counterbalance—an act of both worship and resistance

O believers! Fasting is prescribed for you—as it was for those before you—so perhaps you will become mindful [of Allah]

—The Holy Quran (2:183)

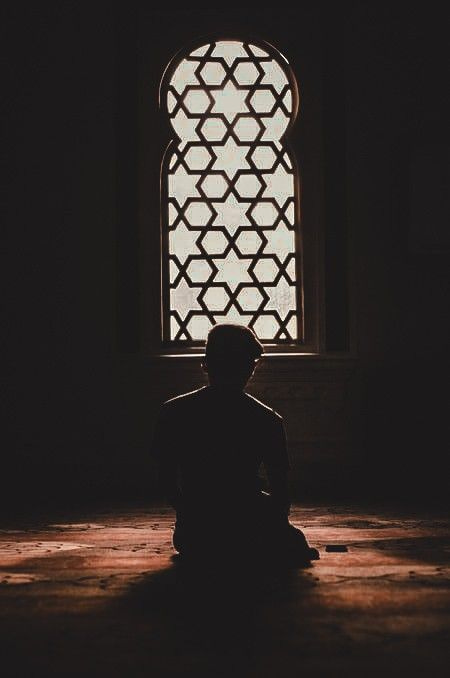

The most precious time of the year for Muslims has begun—a sacred month observed through continuous acts of worship, most notable being the dawn-to-sunset fast.

In my small Lebanese village, fairy lights go up on the front of every store and the verandah of every house a week before Ramadan starts. Young scouts perform a celebratory parade, their hands lifting a flaming fanous or a glittering cut-out of a crescent moon, their voices ringing out in unison as they recite religious nasheeds. People set aside what they’re doing to watch; they stick their heads out their windows, stand by their doors, pull out their phones to access the livestream. A countdown begins in the mind of each of us; our souls, hearts, and bodies yearn for the first day of the blessed month.

As our focus gradually moves from the material to the spiritual, something shifts in the air—there’s a noticeable lightness, an audible calm.

And there’s no better time nor condition for reflection than calm.

Today’s post is a reflection on what Ramadan is probably most known for: abstinence. Drawing on its spiritual value, I argue that, for the modern human, abstinence in the form of fasting has become a necessity.

But before we get into that, I’ve provided a short section below where I explain, for those who may not know, what Ramadan is all about.

Ramadan 101

What it is: Ramadan is the ninth month on the Islamic calendar (also known as the Hijri calendar). It starts when its crescent moon is observed and ends when it is again sighted, twenty-nine or thirty days later.

Why it’s significant: it was during this month, in the year 610 CE, that the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) received his first Quranic revelation through Angel Jibreel (Gabriel).

Why we fast: fasting annually during Ramadan is one of the Five Pillars of Islam i.e. one of the obligatory acts of worship.

How we fast: the fast starts every day at the hour of dawn and ends at sunset (for me, that’s from ~5 AM to 5:30 PM). We wake up for a pre-dawn meal called suhoor, where we eat and hydrate enough to withstand the fast. At sunset, when the call for the maghreb prayer sounds, we break the fast in a meal called iftar.

What we abstain from: during fasting hours, we’re required to refrain from eating, drinking (yes, even water), and having sexual relations. And as in any other day and month, we should avoid sinful behavior, such as lying and gossiping.

The Prophet (peace be upon him) has said that when this holy month begins, the gates of heaven are opened, the gates of hell closed, and the devils chained. It is a time when rewards and good deeds are multiplied manifold. So, in addition to fasting, we avoid wasting time and use it wisely; we read and study the Quran, learn and reflect upon the religion, be of service to others, and develop the most important relationship we have—that with our Creator. We work on becoming better versions of ourselves by practicing kindness, self-control, patience, and mindfulness.

Who fasts and who doesn’t: fasting is an obligation upon every adult and sane Muslim; however, there are exceptions. Those who aren’t required to fast include: the ill, the diabetic, the elderly (if fasting presents any health hazards), travelers until they’ve settled, women who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or menstruating (they resume after their period is over), and children who have not yet reached the age of puberty. But that doesn’t mean that these individuals can’t engage in other spiritual activities—because, as mentioned, Ramadan isn’t solely defined by abstinence; it’s also a time for personal and spiritual growth.

While abstinence during Ramadan is first and foremost an act of obedience to a divine commandment, my experience has also shown it to be a reminder of:

The brevity of pleasure

Man is born needful and dies needful. We live in search of more and different ways to satisfy our needs—the essential and the secondary. Pleasure is the end goal.

Every Ramadan, I find myself in the same situation: while fasting during the day, I’m certain I’ll devour everything available at iftar. But at iftar, I feel full after having some soup and a few bites of the main dish. That dessert I had been craving no longer looks appetizing, and the snacks I had planned to eat feel unnecessary.

It’s interesting and almost unbelievable. How can someone who spent the day hungry and pleasurably thinking of what to eat later become satisfied so quickly?

This has made me realize how brief the pleasure we often spend long dreaming of can be—how temporary and short-lived relief can feel after hardship.

So much so that, if we’re not mindful enough, we may miss it.

The futility of certain things

When we go a whole month being careful of how we spend our time, ensuring that every minute is used for our worldly and religious benefit, we come to see how utterly futile some things are.

A powerful verse in the Quran reads:

And this worldly life is nothing but diversion and amusement. And indeed, the home of the Hereafter—that is the [true] life, if only they knew (29:64)

It gets us thinking—in Ramadan and any other day—whether we’re spending most of our time in diversion. Mind you, there’s nothing wrong with seeking amusement. The human mind can’t survive in perpetual seriousness; a little play, a little distraction, is welcome and necessary to ensure its healthy functioning. But when, for example, our screen time is as high as the number of hours we spend sleeping, that’s how we know we’re living a pastime. That our lives are but an indulgence—a servitude to our unquenchable desire for distraction. So—

Turn off that phone.

Talk to people. Maintain your current ties and make new ones.

Walk around; be of service.

Turn to God and honor the time He’s given you.

Because it can’t be earned back.

How seldom we thank

And We have certainly established you upon the earth and made for you therein ways of livelihood. Little are you grateful (7:10)

Experiencing hunger and thirst first-hand makes us more aware of our blessings, of how readily available sustenance is to us, and of how little we tend to thank. It also fosters in us compassion toward the less fortunate; toward those who, unlike ourselves, have not the choice to abstain.

And it is this concept of choice that I’d like to dwell on in the next paragraphs.

The modern human, of decent income and comfortable livelihood, is perhaps the most severely coddled species to have yet existed. The twenty-first century has ensured that the answer to every whim and desire is within easy reach, thanks to a combination of economic and technological advancements. We no longer have to toil to make purchases or gather in numbers to create entertainment. We find a distraction from our thoughts by losing ourselves in endless scrolling. The satisfaction of something as simple as amusement and as urgent as lust can be found waiting online.

If a name is given to current times, it has to be the age of instant gratification.

Several researchers have criticized this culture out of utter concern for our future. In his 2024 essay “Postpone Your Pleasures,” American author Arthur C. Brooks discusses the psychological benefits of what he calls deferred gratification—the act of deliberately delaying the gratification of our desires for the sake of leading more fulfilling lives. He recommends strategies such as saving money and resisting the urge to immediately spend it, and having structured meals instead of snacking repeatedly throughout the day. These changes can result in the gradual development of stronger self-discipline that’ll allow us to adapt to meaningful, long-term satisfaction over short bursts of immediate gratification.

Because, over time, these short bursts condition our brains to expect a reward or pleasure of some sort as soon as it is craved. We become impatient, emotionally dysregulated. And in the context of technology and social media, this impatience manifests in severely shortened attention spans and our inability—or, refusal—to experience boredom.

But there’s good news.

Since joining Substack, I’ve been met with an abundance of posts and notes encouraging the practice of delayed gratification—by Muslims and non-Muslims alike. There are people asking us to cook our own meals more often and refrain from ordering—to stop and savor the process of turning mere ingredients into delicious dishes. Others are begging us to read a book before watching its adaptation. Even more of them are urging us to develop healthier relationships with our devices—to resist the urge to check our phones at any given moment of inactivity or boredom, to sit back and think for ourselves, to minimize scrolling, slow down and adapt to a life with lower stimulation and more reflection.

People are, in other words, making the conscious choice to abstain from immediate pleasure. They want to reclaim control over their time and lives—they want more mindful, reflective, and present living.

Those before us weren’t plagued by this overwhelming accessibility—this exaggerated ease to satisfy their whims—which means it’s up to us to rewire our brains and recondition them to accept delays. We have to learn how to be patient again.

And fasting is the perfect way to achieve that.

Withholding food when the body needs it. Refraining from wasting time when the mind is begging for a distraction. Forcing the brain to think on its own.

The modern world has presented a problem, but a commandment revealed centuries ago comes as a solution; fasting is how, over the course of a month, we can teach our minds and bodies consistent self-control necessary for spiritual and worldly ends.

I’d like to mention that one doesn’t have to be Muslim to experiment with fasting during this month; I personally have a Christian friend who’s attempted the fast out of interest. I’ve also seen multiple non-Muslim internet personalities joining the Muslim community in this—and they’ve given interesting observations on what changed in their daily lives during that period.

Alternatively, one may practice intermittent fasting, following a schedule a nutritionist can help design.

But as a Muslim who’s becoming more aware of the benefits of the fast, all I have to say is: in a world that constantly pulls us toward indulgence, fasting is not just an act of worship—it is an act of resistance.

Ramadan Mubarak to each and every Muslim reading this! May Allah (the most gracious, the most high) continue to bestow upon us all the chance to experience this blessed month.

For more content on Islam (+ humanities-related topics such as literature, language, and history), consider subscribing to my publication!

And if you’ve resonated with the message in this post, share to spread the word:

Until next week,

Heba

Insightful post! I'm a Christian, myself, but our community also really values the discipline of abstaining, specifically through fasting. You made a lot of great points about how beneficial it can be (even for those of different religions)! Thank you for sharing!