Not caught up? Read the first part of the series here:

“For I know what I should do, but I am afraid of doing it, Boromir: afraid.”

Few of the fantasy books I’ve read have done what Tolkien consistently does in The Lord of the Rings: allow male characters to express emotion. Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves, and Men alike feel what they feel very strongly. In Book Two of the Fellowship, several are the instances in which they weep, and rage, and laugh, and show affection to one another. To places. To things. They put their feelings into verses of poetry that they either committed to memory long ago or improvise on the spot. They communicate them through poignant, romantic tales from Middle-Earth lore.

But at other times, they simply say what they feel. No figurative language to accentuate it. No poetry or tale to romanticize it. Only a direct, unfiltered confession.

By the final chapter, Frodo has witnessed enough of the Dark Lord’s power to force out of him that confession to Boromir: he is, above all things, afraid. He neither denies nor escapes his responsibility; he solemnly accepts that the Quest—this harrowing, perilous Quest—has ceased being a mere adventure. It’s his obligation as the Ring-Bearer.

Book Two takes on a darker tone. The road grows long, and danger dwells in every direction. The dominion of the Enemy expands, and Middle-Earth is cast under its spreading shadow. The Black Riders have dwindled into an insignificant threat now that greater forces—Orcs, Balrogs—chase down the Fellowship. But most vicious is the sting of betrayal—the realization that the power of the Ring can tempt and corrupt even the noble and strong that were once one’s friends.

Book Two is also more fast-paced than the first, and in its two hundred and forty-six pages a lot has unfolded. This second instalment in my LOTR Reading Diaries series takes up the events that struck me most deeply—those that, like the characters themselves, left me both wondering and vulnerable, both shaken and moved.

Reunions, meetings, and the Council of Elrond

True to my prediction in the previous post, Frodo is reunited with Gandalf the moment he awakens in Rivendell. Also in that post I attempted to interpret a dream Frodo had early in the story—that of a white tower beyond which lay the Sea. I wrote of it the following:

The Sea symbolizes Frodo’s success in his quest, and the white tower is a stand-in for Gandalf. At this point in the story, Frodo doesn’t know where his mentor is and whether he is alright, having not seen nor heard from him since before the adventure. That the white tower is situated between dream-Frodo and the Sea is representative of how Gandalf stands in between real-Frodo and the task at hand: the wizard is the means through which the hobbit can achieve success, just as the white tower is the means through which he can see the Sea. The thunder that interrupts dream-Frodo’s climb may be symbolic of an interruption that has seized Gandalf away and separated him from the hobbit. Given the nature of thunder, it’s likely that this interruption is of a dangerous kind—that Gandalf is probably at risk.

My interpretation is validated when the wizard explains the circumstances of his disappearance: while Frodo prepared to leave the Shire, Gandalf sought the advice of Saruman the White, the head of his order of wizards. He had recently discovered the true nature of the Ring and the extent of its powers, and trusted Saruman to offer wise counsel. But Saruman soon proved a traitor: he no longer opposed Sauron’s ambitions. He expressed a desire to wield the Ring himself, and to use its power to defeat Sauron, usurp his dominion, and take over Middle-Earth. When Gandalf refused to conform to this idea, Saruman imprisoned him atop the pinnacle of Orthanc—a mountain so dark and suffocating that it might as well have been a dungeon beneath the earth. Gandalf was eventually rescued by Gwaihir the Windlord, a great eagle, then made his way to Rivendell in time to meet the Company.

It’s appalling how easily a wizard of Saruman’s rank can bend to the Ring’s influence. That it corrupts the mind is a fact established early in the story; but making it that even the wisest give in to temptation adds a far greater urgency to Frodo’s task.

What will be of Middle-Earth if more prominent figures join Sauron’s army?

In Rivendell, an Elf-land where peace still prevails, Lord Elrond promises to hold a Council where the matter of the Ring will be addressed. But prior to the Council there happens a reunion I did not expect at all: that between Frodo and Bilbo. What a surprise it was having Bilbo back so soon!

It’s explained that shortly after leaving the Shire for “a holiday, a very long holiday,” Bilbo went east and arrived at Rivendell. There he was received as an honored guest, and there he stayed to live a quiet life, away from the bustle of Hobbiton—a life spent writing poetry, composing songs, and working on his book (i.e. a life we all want).

You might recall that in Part One I described Bilbo’s departure as suspicious, and theorized that there’s a dark side to him that none know of. Witnessing Frodo’s excitement at seeing the old hobbit again made me want to retract my words and assume I misjudged Bilbo’s character, but this is not yet the case.

There is a moment in which Bilbo expresses temptation, leaving his companion shaken:

“Have you got it there?” he asked in a whisper. “I can’t help feeling curious, you know, after all I’ve heard. I should very much like just to peep at it again.”

“Yes, I’ve got it,” answered Frodo, feeling a strange reluctance. “It looks just the same as ever it did.”

“Well, I should just like to see it for a moment,” said Bilbo.

[…] Slowly he drew it out. Bilbo put out his hand. But Frodo quickly drew back the Ring. To his distress and amazement he found that he was no longer looking at Bilbo; a shadow seemed to have fallen between them, and through it he found himself eyeing a little wrinkled creature with a hungry face and bony groping hands. He felt a desire to strike him.

Hunger. That’s probably the word to make sense of what Bilbo is experiencing. After all, the Ring was in his possession for decades, and in ignorance he made use of it several times. That’s about enough times to leave him craving for it upon separation; enough to leave his heart attached to its mysterious influence. I cannot imagine what role Bilbo will set out to play in the later stages of the story, but for Frodo’s sake I can only hope it’s a good one.

Elrond’s Council happens next. It’s the Middle-Earth version of the United Nations, where folk come representing their lands to discuss current events. Elrond and his group of Elvish counsellors provide what advice they can to help maintain security and avoid conflict—but as the Dark Lord’s power continues to grow, good counsel proves hard to give.

We’re introduced to a few new characters, including Gimli the Dwarf, Legolas the Elf, and a Man named Boromir. Toward Boromir I felt an uneasiness almost immediately, as I felt toward Bilbo, when I read his contributions to the discussion on the Ring.

I don’t deny that he makes a compelling argument, but it is too close an argument to Saruman’s. He suggests that rather than destroy the Ring, the wise and powerful should use it as a weapon to defeat Sauron. His one error is believing that such a move would bring peace to Middle-Earth. Elrond’s counterargument comes instantly: the Ring corrupts a person regardless of their intentions, and if used to defeat Sauron, it’ll only give rise to another Dark Lord.

That Boromir makes this argument even after hearing Gandalf’s story about Saruman (and the fact that he annoyingly counters almost everything Elrond and the others say) marks him as suspicious. Throughout the rest of Book Two, we witness in him a persistent restlessness—a subtly suppressed excitement—whenever the Ring is brought up, until the climactic moment in which he practically harasses Frodo for the Ring and reveals the intensity of his temptation. But I won’t hasten and assume he’s evil, because shortly after Frodo manages to escape him, we see him weep and repeatedly ask himself the likes of “what have I done?”.

Like Bilbo, I’d like to think of Boromir as good, albeit misguided. His fate is something I’m eager to discover: whether he’ll bounce back to his true self or succumb to temptation. Although it would be interesting as a character arc, it would certaintly be heartbreaking if he joined Sauron’s forces; I can’t at all picture him fighting the Company he once swore to protect.

The Council proceeds to answer a question I posed in Part One. You might recall that I wrote about the enigmatic Tom Bombadil, focusing on his perceived immunity to the Ring’s influence. I suggested that Gandalf should have assigned the task of protecting the Ring or destroying it to him, not to a hobbit. An Elf by the name of Erestor, who is Elrond’s chief counsellor, presents a similar question:

“Could we not still send messages to him [Tom Bombadil] and obtain his help?” asked Erestor. “It seems that he has a power even over the Ring.”

“No, I should not put it so,” said Gandalf. “Say rather that the Ring has no power over him. He is his own master. But he cannot alter the Ring itself, nor break its power over others. And now he is withdrawn into a little land, within bounds that he has set, though none can see them, waiting perhaps for a change of days, and he will not step beyond them.”

“But within those bounds nothing seems to dismay him,” said Erestor. “Would he not take the Ring and keep it there, for ever harmless?”

“No,” said Gandalf, “not willingly. He might do so, if all the free folk of the world begged him, but he would not understand the need. And if he were given the Ring, he would soon forget it, or most likely throw it away. Such things have no hold on his mind. He would be a most unsafe guardian; and that alone is answer enough.”

My theory was that Bombadil possesses powers that are only functional within those bounds, but it doesn’t seem to be the case. The fact is that Bombadil is simply withdrawn from the greater issues affecting his world. Actually, his world might not even be the right expression, because his world is restricted to the land he’s mastered and not the broad expanse of Middle-Earth.

One of my dedicated subscribers, Abed Almeneim Shaaban, was closer to Gandalf’s answer than I was—and more impressive is that he hasn’t read the books yet. In a comment he said:

Perhaps it’s the characters who give power to the ring.

If this is indeed the case, then the Ring becomes tenfold more intriguing, because it implies that there is not only a magical aspect to its functionality—but also psychological. Yet nothing’s certain except that Bombadil remains as puzzling as the Ring itself, and that there’s much left unexplored at this point.

The Council of Elrond is the longest chapter in Book Two, and apart from the Ring much else is discussed. Of these topics three stood out the most:

The history of Narsil, Isildur’s sword. It is the sole reason Boromir attends the Council: he has been plagued by a dream in which is repeated a few verses concerning this sword. During the last war against Sauron, this was the weapon that cut the Ring from his hand. Though the sword was reduced to shards then, the dream hints to Boromir that it now rests in Rivendell, and must be reforged for the upcoming war. The shards are indeed brought forth, and the sword is promised to be fixed. But it is not given to Boromir (thank God)—rather, it is Aragorn, heir of Isildur, that later bears it and renames it Andúril, Flame of the West.

The tension between Elves and Dwarves. It is mentioned more than once that there exists enmity among these races, but the exact reason is not told. All that is known up till now is that the Dwarves were somehow responsible for bringing evil to their own (then the Elves’) lands during the previous war. This and the history of Narsil make me so curious about that war: what exactly happened there? Were the Dwarves truly guilty of bringing about harm, or are the accounts told by the Elves merely biased? So many questions. It is, however, heartwarming to see a friendship later develop between Gimli and Legolas, despite their initial quarreling.

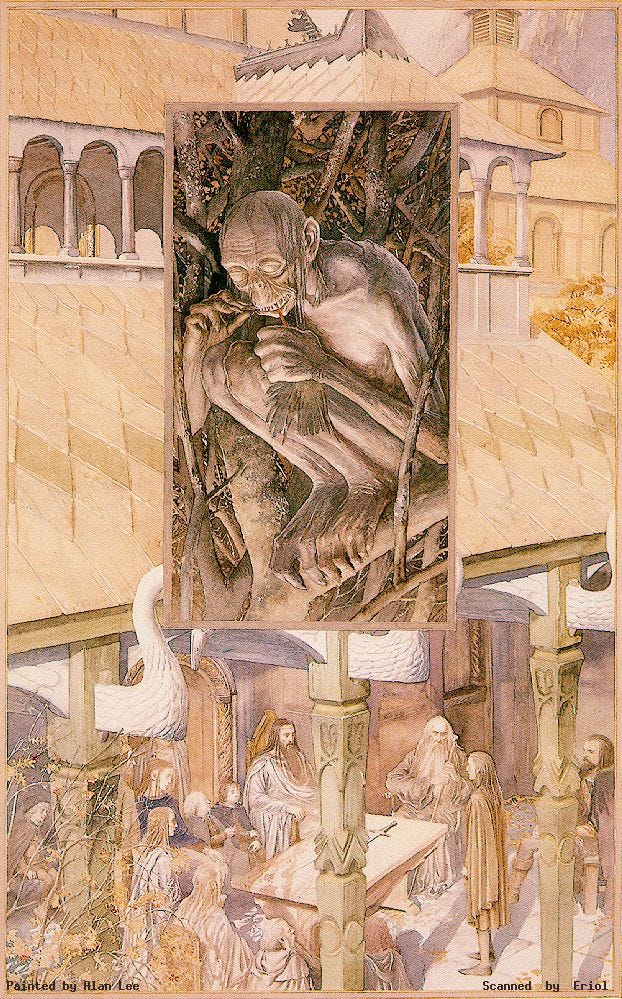

The fact that Gollum has escaped his imprisonment. The creature begins chasing the group after they leave Moria, and his presence is immediately known by Aragorn, and suspected by Frodo and Sam. We haven’t yet seen Gollum interact with or confront any of the main characters, but this—and whatever mischief he will bring about—is something I’m excited for.

If this chapter has proved me anything it is, again, the sheer depth of Tolkien’s worldbuilding. A work of fiction that explores its universe both geographically and historically is bound to be a masterpiece—and LOTR is nothing short of it so far.

Before we continue to other serious deliberations on Book Two, there is one matter that I absolutely have to bring up, and that is:

Why is Gandalf so mean to Pippin?

I understand that Gandalf is characterized as a short-tempered wizard, but why is my boy Pippin always the target of his anger?

In case you’re not sure what I’m referring to, I’ve compiled several instances in which Gandalf roasts the poor hobbit:

(1)

“We hobbits ought to stick together, and we will,” said Pippin. “I shall go, unless they chain me up. There must be someone with intelligence in the party.”

“Then you certainly will not be chosen, Peregrin Took,” said Gandalf.

—The Ring Goes South (chapter 3)

(2)

“But the mountains are ahead of us,” said Pippin. “We must have turned eastwards in the night.”

“No,” said Gandalf. “But you see further ahead in the clear light. Beyond those peaks the range bends round south-west. There are many maps in Elrond’s house, but I suppose you never thought to look at them?”

—The Ring Goes South (chapter 3)

(3)

“What are you going to do then?” asked Pippin, undaunted by the wizard’s bristling brows.

“Knock on the doors with your head, Peregrin Took,” said Gandalf. “But if that does not shatter them, and I am allowed a little peace from foolish questions, I will seek for the opening words.” (poor Pip was only asking!).

—A Journey in the Dark (chapter 4)

(4)

Pippin felt curiously attracted by the well. […] Moved by a sudden impulse he groped for a loose stone, and let it drop. He felt his heart beat many times before there was any sound. Then far below, as if the stone had fallen into deep water in some cavernous place, there came a plunk, very distant, but magnified and repeated in the hollow shaft.

“What’s that?” cried Gandalf. He was relieved when Pippin confessed what he had done; but he was angry [no surprise there], and Pippin could see his eye glinting. “Fool of a Took!” he growled [okay, calm down]. “This is a serious journey, not a hobbit walking-party [whatever even is a hobbit walking-party?]. Throw yourself in next time, and then you will be no further nuisance. Now be quiet!” [I know I would’ve cried].

—A Journey in the Dark (chapter 4)

It’s only hours later, as the party decides to go to sleep, that Gandalf approaches Pippin with an apologetic tone.

“I know what is the matter with me,” he says. “I need smoke! I have not tasted it since the morning before the snowstorm.”

So you’re telling me that the great old wizard was experiencing withdrawal symptoms? It cracked me up, but still—Pippin did not deserve this kind of treatment. I can almost imagine the hobbit smirking smugly as Gandalf fell to his “death” at the bridge of Khazad-dûm. Except that he didn’t. Pippin did the compassionate thing and wept. He’s simply that good for the world he’s in.

Anyway, rant over. Back to the weighty bits of Book Two.

The ambiguous fate of Gandalf the Grey (+ how The Hero’s Journey relates)

I wrote death between quotation marks because I doubt this is the last of Gandalf. Yes, Moria is in many ways terrifying. Yet having him die there would be not only rushed but also a disservice to his character. During the Council of Elrond, Frodo is talking to Bilbo about his adventures, up until the confrontation with the Black Riders at the Ford, when he whispers, “But the story still does not seem complete to me. I still want to know a good deal, especially about Gandalf.”

So do I. To this point little is known about the old wizard, and little has been seen of his power and authority. He has shown to possess control over natural elements, like fire, light, and water, in addition to extensive knowledge of Middle-Earth history, culture, and lore. Although the Orc attack in Moria does challenge him, I think it’s too understated an event to put an end to a character as significant. Gandalf must have found a way to avoid falling to his death, even when there are no pointers yet to this possibility.

In Part One of this series, I compared the progression of the story to The Hero’s Journey—the popular narrative structure described by Joseph Campbell. Throughout Book Two, Frodo and his party experience the phase Campbell refers to as initiation. It’s meant to be the longest phase of any tale, an extended period in which the protagonist is subject to a variety of trials as he nears his destination. Of these trials there have been more than Frodo can bear, and by the final chapter of The Fellowship, he has met allies and foes, but has also witnessed some allies turn to foes. The last scene depicts him making the difficult decision of abandoning his party and leaving for Mordor by himself—a selfless yet incredibly reckless decision. Sam (who is still superior to everyone else), insists on accompanying him. As they embark on the next stage of the Quest, they also enter a sub-phase that Campbell refers to as approach to the inmost cave. This inmost cave isn’t a literal cave; it is symbolic of the most dangerous location in the narrative—i.e. Mordor. It doesn’t include actual arrival, only the final path trodden toward it and the prepwork performed to face the Enemy. This is where Tolkien leaves us hanging for now.

But Campbell writes that at a later point in the narrative, the protagonist is bound to experience a reward—a moment in which he will be seizing the sword. It is that point in which our hero is at his lowest, doubting his ability to fulfill his mission and beginning to lose all hope. But then something happens—something that feels almost magical—to uplift his spirits and breathe courage back into his soul. He sees the light at the end of the tunnel. The reward maybe an object, or some knowledge that the hero is meant to discover, that will help him defeat his enemy. But I’d like to suggest that this reward may also be a person—and that is the role I think Gandalf will play. Reappearing in the most dire moment to offer wisdom and strength that’ll get Frodo back on his feet. His light at the end of the tunnel.

At the end of the day, these forced separations that Frodo is experiencing with his mentor, whether said mentor is alive or dead, have but one purpose: to give Frodo the room to be tested; to grow as a character. While Gandalf was imprisoned by Saruman, Frodo bore the responsibility of leading three other hobbits safely through unsafe locations, before at last handing the leadership over to Aragorn. With Gandalf supposedly dead now, Frodo comes to bear this responsibility again. Except that this time, he will have to rely on no more than himself and his friendship with Sam.

Me? I’ll be patiently reading on, anticipating Gandalf’s return.

Galadriel, Galadriel, Galadriel (try pronouncing this name super fast several times in a row)

The chapter Lothlórien comes as a much needed breather after the loss of Gandalf in Moria. It introduces the reader to an ethereal Elvish realm; a forest imbued with magical light and energy, in which grow, large and homey, trees of an exquisite nature. The party feels immediately mesmerized, desiring nothing but to abide therein for as long as time permits. Although initially tension intensifies between Gimli the Dwarf and the native Elves, this ages-old rivalry becomes trivial once the former succumbs to the beauty surrounding him—a beauty not limited to the mere physicality of the place, but extending to its inhabitants and their kindly manners.

Soon the party meets with the Lord and Lady of Lothlórien. It has to be said that The Fellowship of the Ring gives little space to female characters. It was thus pretty exciting when Lady Galadriel was introduced—charming, yes, but also possessive of a mystifying energy and an undisputed authority over the land and all that roams it.

I’d like to focus on her powers for a moment. Following their first meeting with her, the party retreats to discuss their first impressions—Galadriel this, Galadriel that. They all come to the agreement that they felt unsettled while under her gaze, that she seemed to be “looking inside” them, as Sam relates, stirring in their hearts and minds questions that they dared not answer—questions connected to their deepest desires or most haunting fears. For Sam, for example, it felt as though with her eyes alone she offered him his most pressing wish: to fly back to the Shire and abandon the Quest.

Here Boromir again raises suspicion. He does not reveal to his friends what Galadriel’s gaze felt like on him, does not tell what choice, if any, she seemed to offer him. Instead he resorts to rationalizing her powers:

“To me it seemed exceedingly strange,” said Boromir. “Maybe it was only a test, and she thought to read our thoughts for her own good purpose; but almost I should have said that she was tempting us, and offering what she pretended to have the power to give. It need not be said that I refused to listen. The Men of Minas Tirith are true to their word.”

Two things stand out to me here:

The fact that Boromir is trying to cast a negative light on Galadriel.

That he feels the need to reassure the others of his loyalty.

Aragorn quickly counters his implications by saying: “Speak no evil of the Lady Galadriel! You know not what you say. There is in her and in this land no evil, unless a man bring it hither himself.”

Assuming Aragorn is right (and I do trust him), then Galadriel must have only the best intentions for the group. That said, if she is capable of reading their hearts, or at least sensing their inclinations, doesn’t that mean that she should have been able to detect Boromir’s evil temptations? If she did sense them, why did she not warn the rest of the Company? Either there’s more to Galadriel than she lets on (and than Aragorn knows), or she did not see anything suspicious at all. But this sets forth a contradiction regarding her powers, because later she reveals that she can “perceive the Dark Lord and know his mind.” This means she is capable of feeling evil. My only explanation in her defense is that she might have indeed seen in Boromir that temptation, but also a goodness of heart and the possibility for redemption.

I truly hope hers is not a one-time appearance in the story as, beyond that there’s so much more to know about her, I feel that she might be of use against the Enemy.

Her mirror is another curious thing.

“Many things I command the Mirror to reveal,” she answered, “and to some I can show what they desire to see. But the Mirror will also show things unbidden, and those are often stranger and more profitable than things which we wish to behold. What you will see, if you leave the Mirror free to work, I cannot tell. For it shows things that were, and things that are, and things that yet may be. But which it is that he sees, even the wisest cannot always tell. Do you wish to look?”

(As I read through this section I couldn’t help but wonder if Galadriel’s Mirror is where J.K. Rowling drew inspiration for the Mirror of Erised).

I think it interesting that Frodo and Sam were the only ones offered the chance to look into it, as though she predicted that only the two of them would advance to the next stage of the Quest and were need of some guidance.

What Sam sees is a little disconcerting: a dark cliff under which Frodo lies, pale-faced, with surrounding trees crashing down about him. He interprets it as Frodo being “fast asleep,” but I do wonder if what he really sees is his worst fear—a dead Frodo—but refuses to acknowledge it.

Frodo has two visions: first of the Sea, again, but this time it is caught in a violent storm and a “blood-red sun” is hanging low in the background. I will again interpret the Sea as symbolic of the achievement of his Quest, and venture out to say that what he sees is an upcoming bloodshed. But more interesting is the Eye of the Enemy that follows this vision—haunting, glaring, terrifying. It points to the fact that Sauron is watching him, and has been since the Ring came to his possession.

Struck with fear, it’s understandable that Frodo proceeds to offer Galadriel the Ring. The discovery that she holds one of the other Rings, one of the Three—Nenya, Ring of the Adamant—quickly builds between them a mutual understanding; a sympathy, for both recognize and lament the weight of the responsibility each carries. Galadriel is tempted to accept his offer, but insists that the Quest is his own to fulfill.

The Mirror is a dangerous guide of deeds, says Galadriel, and I wonder how much of what they’ve seen Frodo and Sam will take to heart as they venture out alone.

My previous worries about Sam’s (and Frodo’s) safety have now been doubled. I sincerely hope it doesn’t take Aragorn and the others too long to find them again—at least before disaster.

But for the time being, as I read through The Two Towers, I will remain, like Frodo, afraid.

Memorable quotes from Book Two

“Yet such is oft the course of deeds that move the wheels of the world: small hands do them because they must, while the eyes of the great are elsewhere.” —Elrond.

“For still there are so many things/that I have never seen:/in every wood in every spring/there is a different green” —stanza from a poem recited by Bilbo.

“Faithless is he that says farewell when the road darkens,” said Gimli.

“Maybe,” said Elrond, “but let him not vow to walk in the dark, who has not seen the nightfall.”

“It’s the job that’s never started as takes longest to finish.” —Sam, quoting his father.

“Maybe the paths that you each shall tread are already laid before your feet, though you do not see them.” —Lady Galadriel.

“But do not despise the lore that has come down from distant years; for oft it may chance that old wives keep in memory word of things that once were needful for the wise to know.” —Lord Celeborn.

Thank you for reading until the end of this review! The Fellowship of the Ring is now concluded—and what an adventure this has been! Keep an eye out for the next instalment in this series, where I’ll be dissecting Book Three, the first of The Two Towers.

Until next time,

Heba

What are your thoughts on The Fellowship of the Ring? I’d love to hear them!

Know a LOTR fan who might enjoy this series? Feel free to share!

I wish you would read faster! I've enjoyed reading your insights but I'm afraid if I say anything else I may end up spoiling the story for you.

Pippin is that pain in the butt kid who always does the wrong thing, i.e. the one who sticks a finger into the plug socket or pokes the sleeping bear. He can't help himself. And that just really winds Gandalf up.