Mothers, Boxes, and Impostors

Three exceptional writing tips by John McPhee

If you lack confidence in setting one word after another and sense that you are stuck in a place from which you will never be set free, if you feel sure that you will never make it and were not cut out to do this, if your prose seems stillborn and you completely lack confidence, you must be a writer.

If you say you see things differently and describe your efforts positively, if you tell people that you “just have to write,” you may be delusional.

—Draft No. 4 by John McPhee

It needs to be acknowledged that not everyone gives good writing advice. That is as nuanced an art as writing itself. Still we find the internet inundated with writers who think they’ve cracked the code for all of humanity (thank you, Sally, but the cottagecore playlist that somehow helped you write a sci-fi novel isn’t working for me).

But what makes writing advice “good” in the first place?

I’d say the answer is subjective. From my experience, at least, “good” advice has always been specific, but with room for flexibility. General, yet customizable. It has come from writers who have lived through the same struggles and survived, despite differing circumstances—from people who have shown me the universality of my problems without talking down to me; who have validated my feelings while wisely directing them.

Given the sheer number of success stories out there, you’d think good advice is easy to find. It’s not. A bigger issue is how often said advice earns the exceptional label for the mere fact that it comes from a bestselling author. Never mind that it might be complete bogus—fame entails credibility for many common folk.

Just to be clear, there’s no shame in seeking advice from someone famous. The trick is to find excellence in a haystack of popularity. Pair excellence with humility and you’ve found yourself a reliable guide.

I admit I hadn’t heard the name John McPhee prior to discovering Draft No. 4, an article published in The New Yorker in April 2013. A quick search revealed him as one of the pioneers of creative nonfiction, also referred to as literary journalism. His long-form pieces blend elements of fictional storytelling with factual reporting, resulting in vivid documentations of the many topics, people, and locations he’s covered. Some of his subjects throughout his career include geology, shad fishing, basketball, even oranges. A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize four times, McPhee earned it at last on his fourth run in 1999 for his book Annals of the Former World—an extensive exploration of North American geology along the 40th parallel, written over two decades and during much traveling across the continent. He began writing for The New Yorker in 1965, and it’s where several of his long-form articles appeared before being expanded into books.

Draft No. 4 is an essay in which McPhee opens a frank discussion about writing, focusing on the enemy most detested by writers of all ages and levels alike: block. This word is in fact how he opens the piece:

Block. It puts some writers down for months. It puts some writers down for life. A not always brief or minor form of it mutes all writers from the outset of every day.

The advice he offers in it doesn’t come with an I’m-better-than-you-so-listen-closely attitude, but with an I-feel-you-and-can-help-you one. He is gentle in the way he addresses the reader, delivering each tip through anecdotes and conversations he’s had with his daughter Jenny, who has always wanted to be an author. In other words, he speaks to the reader as he once spoke to her—and how can one doubt the sincerity of a father’s words to his own child?

Another remarkable aspect is that while his advice is universal, it can be adjusted to each writer’s condition, making it a prime example of good writing advice.

In 2017, McPhee compiled this essay with several others into a book he titled Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process. This post discusses three writing tips featured in the eponymous article. You will find that, although McPhee writes nonfiction, these tips can be applied to virtually any kind of writing you undertake.

Tip #1: Your mom is the antidote for writer’s block

You are writing, say, about a grizzly bear. No words are forthcoming. For six, seven, ten hours no words have been forthcoming. You are blocked, frustrated, in despair. You are nowhere, and that’s where you’ve been getting.

What do you do?

You write, “Dear Mother.” And then you tell your mother about the block, the frustration, the ineptitude, the despair. You insist that you are not cut out to do this kind of work. You whine. You whimper. You outline your problem, and you mention that the bear has a fifty-five-inch waist and a neck more than thirty inches around but could run nose-to-nose with Secretariat. You say the bear prefers to lie down and rest. The bear rests fourteen hours a day. And you go on like that as long as you can. And then you go back and delete the “Dear Mother” and all the whimpering and whining, and just keep the bear.

The first draft is where a writer’s dread lies. The act of creating it is one of intense psychological labor, the origin of all despair. It’s slow and clumsy, and it has you doubting your capacity to conceive a single coherent sentence. You’ll write one, but then erase it. You’ll write it again, erase it again. You’ll think of a better introduction and write it down, but it’s either too on-the-nose or irrelevant to what you have to say. You’ll erase it.

The key to progressing in a first draft is to overcome the urge to replace what you’ve written. It might be trash, yes, but at least trash is something that exists.

“How can someone know that something is good before it exists?” asks McPhee.

He shares that one day, as he drove Jenny to school (she was a senior at Princeton High School at the time), she confessed she was feeling incompetent because of how long it was taking her to finish some writing assignments. It worried her that she wasn’t getting things right the first time.

“The way to do a piece of writing is three or four times, never once,” he replied to her. “For me, the hardest part comes first, getting something—anything—out in front of me.”

This is where the Dear Mother approach to writing comes in handy. The first step is to choose someone you’re comfortable blurting, heaving, babbling out something—anything—to. It could be your mother, or father. A sibling, or friend (even an imaginary one counts). It has be someone you’re fine being messy around. Incoherent.

Once you’ve made your choice, write “Dear [name],” and fling at the page whatever comes to mind. Make it sound like you’re ten again, speaking your mind to your diary. But regardless of what you start with, you eventually have to address the writing task at hand. Complain about how hard it is, then write what you know of it so far. By the end of it, you’ll find you’ve written more than you thought possible.

And that is your first draft.

“With that,” writes McPhee, “you have achieved a sort of nucleus. Then, as you work it over and alter it, you begin to shape sentences that score higher with the ear and eye.”

Keep altering, and you’ll have a second draft. The time between one stage and the other is sometimes expected to be long. McPhee admits that the first draft for a long piece he wrote on California geology took him two gloomy years; the second, third, and fourth drafts were all completed in six months. But that is not in any way the standard. I finish first drafts in one week, usually, and editing takes a couple of days—sometimes just a few hours, depending on the length and complexity of the piece. To each their own pace.

What matters is that, thanks to your mom (or another loved one), that terrifying monster called writer’s block can be defeated, buried, and forgotten.

Tip #2: Box your uncertainties

McPhee claims that each writing phase involves a different psychological state. The first draft, which in Poe-tic fashion he refers to as the pit and the pendulum stage, is characteristically one of despair—the sense of emptiness and relentless pressure felt by the writer are but natural consequences. But once it is finished, a different person takes over; the dread disappears, and the problems within the draft become less of a threat and more of a challenge.

You have fixed the overall organization, and now you have a second draft. You proceed to edit the specifics: rewriting sentences, fixing their structures, eliminating the irrelevant and unhelpful, and tightening your prose. You have a more polished third draft. But you’re still not satisfied.

The next step, according to McPhee, is to box your uncertainties.

Read through your third draft. You are likely to notice words that don’t quite work. Words that don’t sound right where you’ve put them, even if they fulfill their purpose. Some other word in the universe might be a better fit. The solution is to enclose those words in a box (or a highlight, if you’re a modern human) as soon as you spot them. Keep doing that until the end, then return to the boxed words, one by one.

“I go searching for replacements for the words in the boxes,” writes McPhee. “The final adjustments may be small-scale, but they are large to me, and I love addressing them.”

How, exactly, does one find the perfect replacement for each word?

It’s tempting to look at a thesaurus, type down the word in question, and select a synonym among those listed. But here McPhee begs the reader to take caution, for thesauruses can be dangerous.

No, no, not for that reason (although that too is terrifying).

The problem with thesauruses is that they can induce the writer to choose a complex, polysyllabic word instead of a simpler one. It makes them susceptible to sacrificing clarity for the sake of a more advanced vocabulary (or the impression of it)—an act deplorable to most editors. The result is fuzzy language, and the reader spends the time meant for engagement searching up definitions instead.

Another issue McPhee points out is that thesauruses don’t talk about the words they list. Dictionaries, on the other hand, are of two types, and one of them tells you the subtle differences existing between one word and its synonym. That’s the kind you want to use. It’ll tell you, for example, how “fidelity” differs from “loyalty”, and how that in turn differs from “devotion.”

McPhee offers an example from one of his own works. Having grown up riding canoes across northern lakes and forest rivers, he one day found himself writing a piece on why a modern person should consider covering a long distance by canoe and not another, faster form of transportation.

I was damned if I was going to call it a sport, but nothing else occurred. I looked up “sport.” [in the dictionary] There were seventeen lines of definition: “1. That which diverts, and makes mirth; pastime, diversion. 2. A diversion of the field.” I stopped there.

The outcome in his final draft was as such:

“His professed criteria were to take it easy, see some wildlife, and travel light with his bark canoes—nothing more—and one could not help but lean his way. I had known of people who took collapsible cots, down pillows, chainsaws, outboard motors, cases of beer, and battery-powered portable refrigerators on canoe trips—even into deep wilderness. You set your own standards. Travel by canoe is not a necessity, and will nevermore be the most efficient way to get from one region to another, or even from one lake to another—anywhere. A canoe trip has become simply a rite of oneness with certain terrain, a diversion of the field, an act performed not because it is necessary but because there is value in the act itself.”

Notice the power this simple change has over the paragraph. “Sport” might have captured the entertainment aspect of canoeing, but not the visual element—that of practicing such sport in an outdoor, natural space. It fails to combine those two factors as “a diversion of the field” does, and thus makes an incomplete and unpersuasive argument in favor of canoeing. All it took was one closer look into a dictionary.

That said, McPhee doesn’t altogether discourage the use of thesauruses. Yet he insists that they be used only for assistance, and that it always be followed by your use of a dictionary. He reflects on how writing and journalism courses tend to frame thesauruses as writers’ crutches, implying that no competent writer should rely on them entirely.

“At best, thesauruses are mere rest stops in the search for the mot juste,” he writes. “Your destination is the dictionary.”

Having used a dictionary to replace all the words you’ve put in boxes, the writing is done. Your piece has reached its fourth draft, and every word and sentence serves the function you intended it to serve. It is ready for the world to see.

And yet, doubt lingers.

Tip #3: Allow yourself to be an impostor

To feel such doubt is a part of the picture—important and inescapable. When I hear some young writer express that sort of doubt, it serves as a checkpoint; if they don’t say something like it they are quite possibly, well, kidding themselves.

Jenny was twenty-three when she reached out again about her writing. She complained that her style was always similar to what she was reading at the time, and that it felt “overwhelmingly self-conscious and strained.”

“How unfortunate that would be if you were fifty-four!” replied McPhee.

He goes on to discuss a matter I’ve addressed in one of my articles: that young adulthood is a foundational period for the serious writer. That a young one’s style should imitate that of others—of excellent others—is not only natural but important. It might feel wrong, yes—criminal, even—to imitate, though it so often happens unintentionally, but it is when the amateur looks up to excellence and attempts to mirror it, weaving it into the fabric of their own creations, that their unique voice begins to take form. It is a years-long process, but slowly the elements of imitation start to fade away. The prose starts to relax; becomes less self-conscious. It starts to become yours.

“Practice taking shots at it,” he adds. “A relaxed, unself-conscious style is not something that one person is born with and another not.”

Here I’m reminded of Stephen King. In his memoir, On Writing, he admits that his work as a teenager was a “pretty fair imitation of H.P. Lovecraft” and, later in his young adulthood, a “bad imitation of John D. MacDonald.” The years passed on and, with consistent practice and more imitation, he found and developed his own voice by blending pulp storytelling with his everyday-American perspective.

So ask yourself: whose work am I reading now, and how can my writing benefit from it? Experiment with their style. Adapt to it. See if it works for you, and do something similar from scratch. Search for excellence and draw from it. Absorb it. Consume it. Allow yourself to feel like an impostor, a cheat. Do it until it becomes an essential part of your writing, then watch as it slowly fades, year by year, until it is replaced by a voice you might not recognize at first—an original, unique, raw voice that is unapologetically yours.

I think what this advice is ultimately trying to convey is a fact many of us writers tend to forget: that writing is a lifelong adventure. It’s not something you master overnight, but something you discover over the years. It requires you to show up in every season of your life until your writing itself becomes seasoned. Your prose is a forever friend that finds itself as you venture out to find yourself. It develops as you develop. It’s there for you in your brightest and darkest days.

Oh, and I almost forgot to tell you: Jenny McPhee grew up to become a successful novelist, having published three by 2013.

Her father’s advice worked for her. It might for you, too.

If McPhee was able to address so much of writers’ doubts and fears in an eight-page article, I can’t imagine what more his 200-page book has to offer. Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process now sits as one of the top titles on my TBR list.

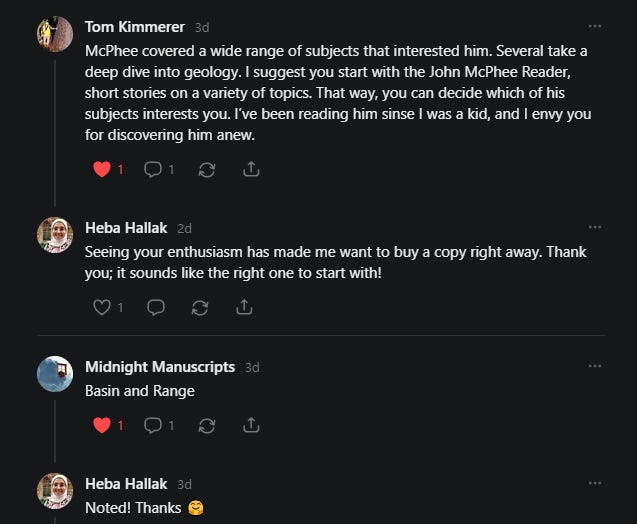

But I know I won’t be satisfied reading just his advice. This is why I recently posted a Note asking for directions on where to start with his creative nonfiction—even though that is a genre I don’t usually pick up. A couple of you have so kindly replied—thank you!

But for the time being, I will be applying these three tips to my writing—both fiction and nonfiction. I in fact applied them to this post as I wrote it, and I kid you not when I say my writing felt twice as fast and enjoyable as before.

Remember your mom, box your uncertainties, and don’t be afraid to be an impostor (and enjoy this phase while it lasts!).

Until next time,

Heba

Have you read anything by McPhee? Let me know what you think of his writing:

And don’t forget to share this post with anyone you think might benefit from these tips!

Thanks for posting - it was an interesting read

Thank you for writing this, and introducing McPhee to us! ☺️ It's always a pleasure to read your work. I really enjoyed reading this, it has a nice witty tone to it. Tip 1 is my favorite. Hopefully, I'll be able to apply this in my writing as well. 🍀