Byblos, the Phoenician Alphabet, and Me

How an unexpected trip got me obsessed with an ancient script

Let’s start this post with a fun little exercise: write your name in Phoenician!

I’ve provided the symbols and their corresponding sounds below for your convenience. Copy-paste them and share your name in the comments (or write on a piece of paper and attach a picture of it for me to see).

But before you do so, keep these instructions in mind:

1- Unlike English, you should write from right to left.

2- You may not find all the symbols you need (I discuss this in a later section). Use what’s available.

3- Some of what you’ll find are sounds that don’t exist in English, but they do in Semitic languages like Arabic and Hebrew. I’ve identified them and included links to videos pronouncing their equivalents in Arabic.

Now, let’s see what your name looks like in this ancient script!

The Phoenician alphabet

The glottal stop sound as in ne[t]work (American pronunciation) and uh-oh → 𐤀

The sound [b] as in ball → 𐤁

The sound [g] as in goal → 𐤂

The sound [d] as in door → 𐤃

The sound [h] as in help → 𐤄

The sound [w] as in wall → 𐤅

The sound [z] as in zoo → 𐤆

The sound [ħ] → 𐤇 (doesn’t exist in English, but it sounds like this)

The sound [ṭ] → 𐤈 (doesn’t exist in English, but it sounds like this)

The sound [y] as in yes → 𐤉

The sound [k] as in cat → 𐤊

The sound [l] as in long → 𐤋

The sound [m] as in make → 𐤌

The sound [n] as in no → 𐤍

The sound [s] as in sun → 𐤎

The sound [ʕ] → 𐤏 (doesn’t exist in English, but it sounds like this)

The sound [p] as in police → 𐤐

The sound [ṣ] → 𐤑 (doesn’t exist in English, but it sounds like this)

The sound [q] → 𐤒 (doesn’t exist in English, but it sounds like this)

The sound [r] → 𐤓 (this is the trilled r sound, pronounced here)

The [š] sound as in shoe → 𐤔

The sound [t] as in table → 𐤕

For funsies, I did it and the phonetically closest way to write my name (which sounds like this) is: 𐤄𐤁𐤄

Ruins, relics, and letters

Note: all the pictures shown in this section were taken by yours truly.

Despite having lived in Lebanon for fifteen years, I only became interested in learning about the Phoenicians after an unexpected visit to the Byblos Citadel last year.

As a university student, I would receive a monthly email from the Student Life Office informing of an organized trip. Sometimes the destinations were catered to the interests of specific majors, and sometimes they were general enough that anyone would be compelled to sign up. Being admitted, however—that was rare. The trips had a very limited student quota and, depending on their nature and educational value, some majors were given precendence to others.

After I was denied a visit to a famous TV studio (though I pursued a minor in journalistic writing), to a renowned skincare products factory, and to Lebanon’s oldest archaeological museum, I came to accept my bitter fate as a lifelong member of the Trip-Deprived Club.

But when, during my final semester, an email reached me with an invitation to the Byblos Citadel, I chose to hope, for the last time, that they’d consider me for their highly classified roster of the Admitted—the Office’s attempt at a reconciliation.

I signed up with my friend, neither of us thinking seriously of that possibility. But another email the night before the trip proved us both wrong.

With hardly any concern over the lectures we’d miss, we seized that rare chance and found ourselves filing into the university bus the next morning. What was supposed to be an ordinary Thursday—a day packed with academic responsibilities—became an extraordinary day spent frolicking in one of the most ancient archaeological sites in all of the Levant—and the world.

As a city, Byblos (Jbeil in Arabic) is located on the central coast of Lebanon and has been continuously inhabited since at least 7000 BCE. Some of the most notable civilizations that have taken over its rule are, chronologically:

The Canaanites, then their descendants, the Phoenicians (approximately 3000-333 BCE).

The Ancient Greeks (roughly 333-64 BCE)—a rule achieved after Alexander the Great’s conquest of the city.

The Byzantines (395-637 CE), who converted Byblos from a pagan to a Christian city.

Islamic Caliphates (637-1104 CE) from the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid dynasties, who in turn spread Islam in the land.

The Crusaders (1104-1289 CE), who fortified the city by building the Citadel.

The Mamluks (1289-1516 CE), who in turn destroyed much of the Crusaders’ work.

From then on, the city saw the arrival of the Ottomans and its integration into their Empire until the year 1918, the undoing of that Empire and officialization of the French Mandate in the mid-twentieth century, then its gradual development into the modern city it is today.

Under Phoenician rule, it was a significant center for maritime trade with the ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Greek civilizations. Cedar wood, purple dye, and papyrus were amongst the products most exported. In fact, the etymology of Byblos as a name leads us to the Greek word bublos, which means papyrus; so much had the Greeks come to associate the city with this product that they managed to rename it. Previously, the Phoenicians referred to Byblos as Gubla or Gibelet. While the exact meaning of these words is unclear, some linguists suggest that—since Phoenician was a Semitic language—they may have been based on the Semitic word root G-B-L, which could mean “boundary” or “mountain.” Gubla and Gibelet may thus have meant “border town” or “hill/mountain town.” Because the city is located between the Mediterranean coast and the foothills of Mount Lebanon, both possibilities come to make sense.

This trip was not my first to Byblos nor its citadel, but it was my first guided one.

Upon arriving, a friendly-looking old man approached our group—bushy white eyebrows, a balding head, reading glasses hanging round his neck. He smiled, introduced himself as the guide, and began walking us through the place and its history.

But he didn’t just tell us its history. He narrated it. Passionately, precisely.

As I listened, it was easy to let my imagination loose, and I was taken all the way back to the 12th century CE. I could see Crusader warships arrive at the coast, their cross-bearing flags soaring against the wind, soldiers spreading about to claim the city as their own. Where I stood outside, I could hear them scheme and decide upon the building of a seaside fortress—a sprawling castle with numerous watch towers, needed for surveiling the Mediterranian waters. I could see them set out to work, collecting large limestones once used as the building blocks of Phoenician and Byzantine structures, reusing them for the construction of their citadel.

Entering its darkened halls, with nothing but the guide’s detailed and often humorous narrative ringing in my ears, I peeked into what used to be living quarters, storage rooms, and chapels. I could see a leader gathering his followers in one of those rooms, giving some sermon, instructing on future trade and military strategies. Then, in obedience to their leader, I saw Crusader soldiers taking turns on top of the towers, their eyes ever watchful of the coast.

Once outside again, eyeing the half-damaged columns by the sea, I saw mighty Mamluk armies descend from their ships onto the shore. They spread rapidly, their voices roaring out aggressively, to surround the citadel. Their trebuchets and mangonels began hurling large rocks here and there, until the fortress came partly down, ending the Crusader rule over the Lebanese coast once and for all.

One of the last stops during the trip was a room furnished with ancient Phoenician relics, each encased protectively within glass boxes. I walked past an odd-looking urn in which lay the remains of a Phoenician baby (yep). The guide explained that this method of child-burial, known as amphora burial, was common to their civilization. It held a spiritual significance that historians differ on nowadays, but one explanation is that the round urn was meant to symbolize the safety of a mother’s womb. That, according to pagan Phoenician belief, could provide some sort of protection to the deceased baby in the hereafter. Small offerings, such as amulets and figurines, often accompanied the remains in the urn. He showed us some of these figurines in a separate section of the room.

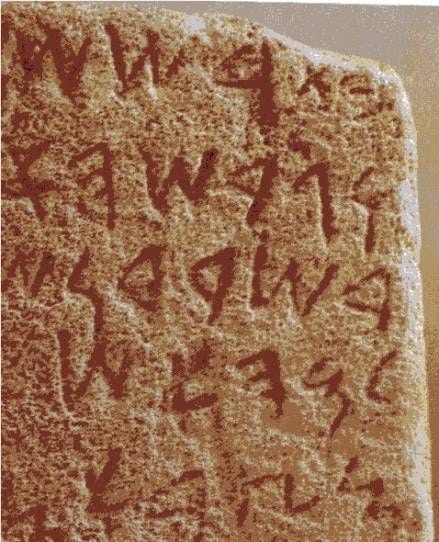

At last, the guide stopped by a desk that displayed the well-known Phoenician alphabet. He regarded us silently for a long moment and narrowed his small eyes as if in deep thought.

Then he spoke. Not in Arabic or English, but in Phoenician. We listened in awe to the incomprehensible but oddly familiar combination of sounds, and to this day, I beat myself up for having forgotten to record him.

He laughed when he finished, then challenged us to translate as many words as we could. Our faces and minds were blank until he revealed he had been reciting a Phoenician translation of the English text on our brochures.

I was fascinated, so I set out to learn more about the civilization that was once mighty and thriving in my country. And of everything I’ve read, the alphabet is what has most interested me.

In the section below, I go over some of the things I’ve learned about the Phoenician alphabet, then reflect on the status the Phoenician language would have in modern-day Lebanon if it were ever to be revived.

The Phoenician alphabet is cooler than you think

While writing your name in Phoenician script, one of the first things you might have noticed is the lack of vowels. The alphabet consists of 22 letters, the a, e, i, o, and u sounds missing.

But that’s not because vowel sounds didn’t exist in Phoenician speech (I don’t think consonant-only speech is even possible). It’s because the Phoenicians simply did not need to represent them in their writing.

And there are a couple of reasons for that:

The structure of Semitic languages

As previously mentioned, Phoenician was a Semitic language like Arabic and Hebrew. This family of languages relies on root-based morphology—a linguistic system where words are formed by inserting vowels into a meaningful set of consonantal roots.

But ignore the jargon and take this analogy: a word in Semitic languages is like the human body—it is formed by inserting flesh (vowels) into a skeleton of consonants. Most skeletons consist of three consonants that denote a specific meaning.

For example, the root/skeleton K-T-B is related to the act of writing.

In Arabic, inserting different vowels into that root creates different meaning:

K-a-T-a-B-a means “he wrote”

K-u-T-i-B-a means “it was written”

K-i-T-a-B means “book”

Similar was the case for Phoenicians in their language. In speech, the vowels were well pronounced. But in writing, the vowels were omitted and only the consonantal roots were kept. Native speakers would read the sentences, derive the context, and accordingly figure out the intended vowel sounds and what the passages meant.

Pretty cool, huh? Albeit difficult. As a native speaker of Arabic, if the vowels were to be omitted in writing, I think it would become much trickier for me to fully grasp the correct meaning.

Practicality and efficiency

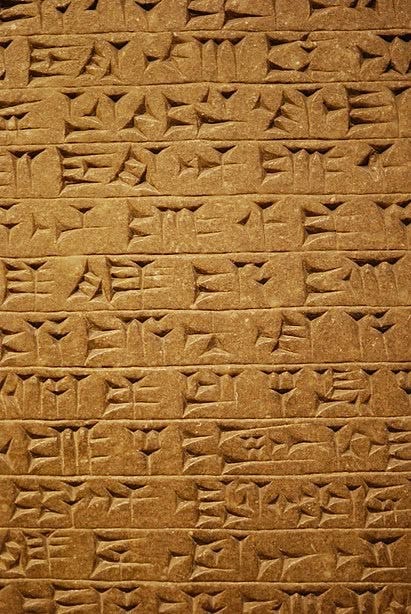

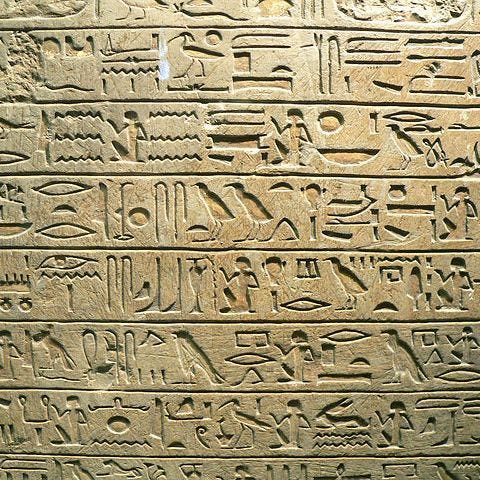

The Phoenician script was, to an extent, influenced by earlier forms of writing like cuneiform and hieroglyphics. But these two were syllabic or pictorial representations of meaning, and so included hundreds of symbols. Phoenicians, on the other hand, managed to represent meaning with just 22 phonetic symbols. Also unlike the other two, Phoenician script was defined by simple-looking letters, angular and linear in shape—so much easier to reproduce than the complex, wedge-like structures of cuneiform and the detailed hieroglyphic symbols.

Can you imagine being Sumerian and having to memorize over 600 of these cuneiform shapes?

Or having to start an art project every time you wanted to write to an ancient Egyptian friend?

Don’t get me wrong—I’m a huge fan of old scripts like these and love learning about them. But if we’re talking about practicality, then they’re out of the question.

The Phoenicians must have thought so, too.

Having developed a purely phonetic alphabet with doable, easy-to-learn shapes already facilitated things for them. Omitting the vowels was just another step in that direction—it meant having fewer letters to commit to memory.

Imagine you’re a Phoenician merchant caught up in the hustle and bustle of a fair. You feel the need to inscribe labels on your goods. You have limited space for writing, which means you’ve got to communicate only the essentials. And you need to do it quickly, otherwise you’ll lose that impatient customer.

The 22-letter alphabet based on consonantal roots makes this possible. With just three or four consonants per word, written in fast and simple strokes, you communicate the root of your message.

From what we can see, then, the omission of vowels wasn’t a flaw in the Phoenician alphabet. It was an ingenious feature that made writing practical and efficient for a trade-centered civilization.

During my readings, I found other interesting quick facts about this alphabet. They include:

The belief that the Phoenicians invented the first alphabet isn’t entirely accurate. Earlier alphabetic systems existed, like the Proto-Sinaitic script (an adaptation of Egyptian hieroglyphic symbols into a phonetic system) and the Ugaritic alphabet (a 30-letter cuneiform script that included vowels). But the Phoenician alphabet was different—it was simpler, purely phonetic, and easy to learn. Most importantly, it spread far and wide, thanks to Phoenician traders who carried it across the Mediterranian.

So while the Phoenician alphabet wasn’t the first, it was the most influential, directly shaping the Greek and Hebrew alphabets and, through them, influencing Latin and Arabic. It’s kind of like how the iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone, but it revolutionized mobile communication.

It was accessible. Earlier forms of writing, like cuneiform and hieroglyphics, were in their respective civilizations the privilege of a social elite. Scribes, administrators, religious leaders, and other important-slash-powerful individuals had the advantage of being literate. But the Phoenicians’ invention of a simpler alphabet for trade and everyday use helped spread literacy further in society, allowing ordinary people to master written communication.

The word alphabet itself comes from Phoenician. Sure, its two syllables come from the Greek words alpha and beta, but the Greeks actually derived these words from the Phoenician aleph and beth—which are respectively represented by the 𐤀 and 𐤁 symbols.

I know, I know: the Phoenician alphabet really is cooler than one might initially think. If you’d like to learn more, I’ve included links to detailed readings at the end of this post.

For now, though, let’s move on to some reflecting.

If revived, would the Phoenician language have a place in modern Lebanon?

That’s a thought that doesn’t leave me. My Roman Empire.

Reviving the Phoenician language is of course a highly hypothetical scenario. It’s true that Hebrew, also a Semitic language, has been successfully revitalized—its status has transformed from purely the language of the Torah to the everyday language of Jews around the world. But there are difficulties and intricacies to reviving Phoenician that aren’t applicable to Hebrew’s case. I won’t be going into this now; instead, I’d like us to suppose that somehow Phoenician has already been brought back from the dead and is ready for common use.

In this case, it would be integrated into an already diverse linguistic landscape characteristic of today’s Lebanon: the Constitution states Arabic is the only official language, but the use of French has persisted in education, business, and even in government—the undying legacy of the French Mandate. English, being the universal language it is, has also seeped its way into everyday interactions among the Lebanese and is the main language of several institutions.

With that said, any given Lebanese person is at least bilingual and commonly trilingual.

But this landscape is also quite complicated, because using each of Arabic, French, or English comes with certain social nuances and implications. The language you speak in your interactions can give others impressions (mostly inaccurate) about your upbringing, education, and values.

Speak mostly Arabic and you’re likely Muslim; speak mostly English or French and you’re likely Christian.

Speak Arabic and you’re likely from the rural regions, brought up with traditional ideas; speak English or French and you’re likely from the capital, brought up with sophisticated Western ideas.

In his article, “Lebanon’s Language Dilemma,” Jonathan Lahdo puts the issue nicely in this passage:

In Lebanon, there’s a prestige complex. Mothers berate their children for saying ‘شكراً’ (shukran) in public for fear that they may be judged for not using the socially acceptable ‘merci’. The Arabic language is now associated with an almost ancient, uncivilized past and is not well thought of by the many Lebanese that take pride in speaking foreign languages instead of Arabic.

It’s a bleak reality we’re living. The use of Arabic in the country has been on a decline for a while now; I have friends from college who have lived their whole lives in Lebanon but can’t speak a word of it, let alone read it. And they show no interest in learning. It could be prestige, as Lahdo writes, but it also could be a desire to dissociate one’s self from the Arab identity. Given the current state of the Arab world—political, economic, social—many Lebanese claim to have enough reasons to feel apathetic to and even embarrassed about being Arab. And because language is central to identity, they purposely avoid it.

How, then, does adding the Phoenician language to the mix affect these existing dynamics?

I’ve reflected on this matter for some time, and these are the possible outcomes I can imagine:

If we’re being optimistic: the Phoenician language could awaken a sense of shared cultural heritage, a sense of community, in a society that is already way too divided. It could come as a common ground—a medium of communication void of social implications. The language for neutral interactions, for when the Lebanese are not looking to be biased.

If we’re being pessimistic: the Phoenician language, if not made accessible to all the public, could create yet another division. Those who speak it would pass as members of an enlightened elite (kind of how the scribes and important people in some ancient civilizations were), adding another layer of prestige. More linguistic animosity. A new option for those hoping to detach themselves from their Arab identity.

If we’re being realistic: most of us would not put in the effort to learn it. It would be more of a symbolic revival, similar to how Old Norse, Sanskrit, and Latin are used nowadays by their countries of origin. Phoenician script would be used for official mottos, appearing on national symbols, school and university crests, perhaps as elective language courses for nerds like me and you, on touristic campaigns and maybe even Lebanese pop culture. It would, in other words, become a historial and cultural symbol for Lebanon without disrupting everyday life—its integration into daily interaction deemed unnecessary.

A revival of Phoenician is improbable for many reasons (but hey, a nerd can dream, right?). Regardless of whether it does happen at some point in the distant future, one thing remains clear: Phoenician history—particualrly its script—is fascinating and will continue to fascinate generations to come the more language evolves.

For more information

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Phoenician-alphabet

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/first-rulers-mediterranean/

https://www.worldhistory.org/phoenicia/

What do you think of the Phoenician alphabet? Share your thoughts below!

Oh, and don’t forget to show me what your name looks like in it!

Also, if you liked this content, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive more like it:

Until next week,

Heba.

Thank you for taking me on the trip with you through your writing :-D

This was fun to read!

As for Phoenician, I find that it’s older than the Greek alphabet and it influenced the scripts that came in the following centuries.

How Phoenician was written is very similar to how Baybayin used to be written, the ancient Tagalog script. Consonants only and no vowels. It wasn’t until the Spanish era that vowel diacritics were added ironically.

The way you mention language as a social status in Lebanon also rings true in the Philippines. You mentioned how the urban elite know French and some don’t know Arabic and if they speak mostly Arabic, they’re mostly conservative and religious and from the rural area. It’s kinda the same in the Philippines. The rich make sure their kids speak English as a first language and don’t know Tagalog or any local languages. They use it as a status symbol. English is put on this pedestal like how French and English are in your country. It’s sad that’s how the state of languages are.

I hope to read more!